From time to time, the Her Hacks team likes to get out of the hack mines, get some sunshine and have a couple of margaritas (frozen, of course) while enjoying a warm breeze.

And sometimes they are pulled out of the mines, put in a library and told to find some hidden gem authors.

Both are equally valid vacations and, spoiler alert, today’s hacks are of the latter variety.

Literature might seem like a welcoming field for women in the 21st century (a debatable claim that goes beyond the scope of what we’re discussing here), but that hasn’t always been the case.

While the case of women authors using initials instead of names is a common practice today — we know Ms. Rowling, of “Harry Potter” fame as J.K. instead of Joanne because her publisher thought it would attract more boy readers — male pseudonyms were a common practice for women to get published, as well.

The Bronte sisters — Charlotte, Emily and Anne — used male pseudonyms — Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell — on their works throughout Emily and Anne’s lives, for instance.

So, in honor of the feminine contribution to the written word, the Her Hacks team has compiled a list of female authors who are worth tracking down and reading.

Of course, we can’t cover every worthy writer in this article, but those who follow are a good sampling to get you started on your journey to literary Nirvana.

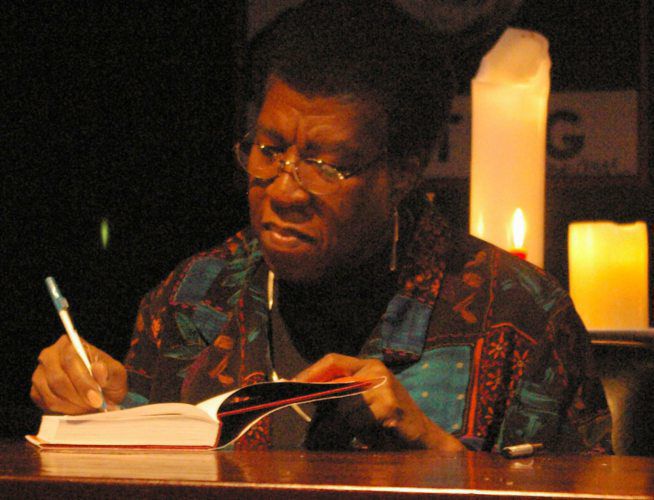

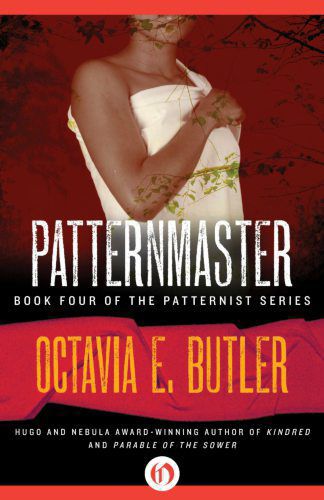

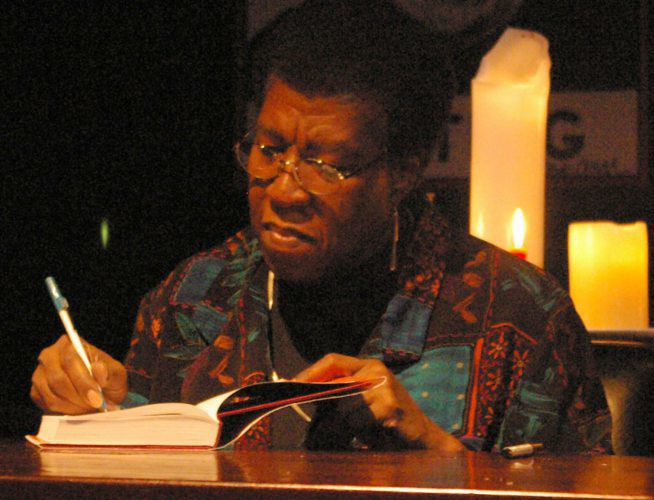

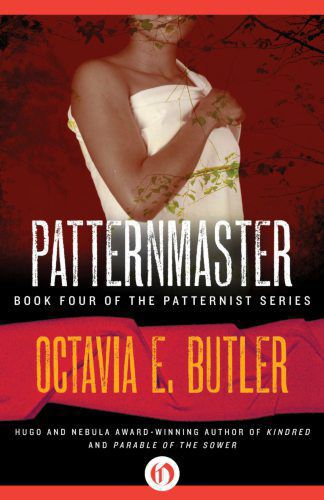

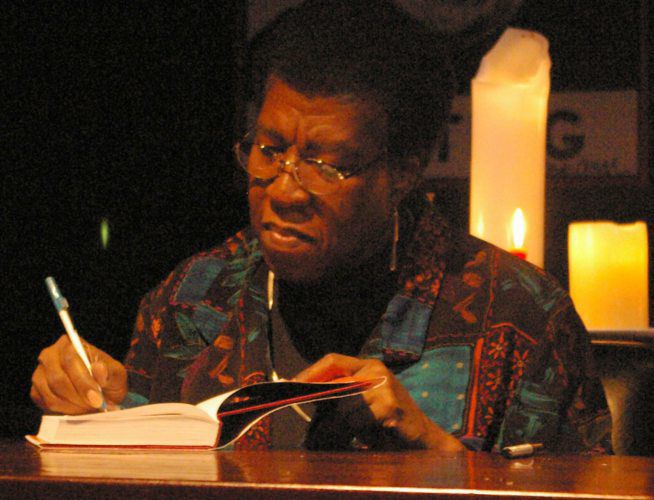

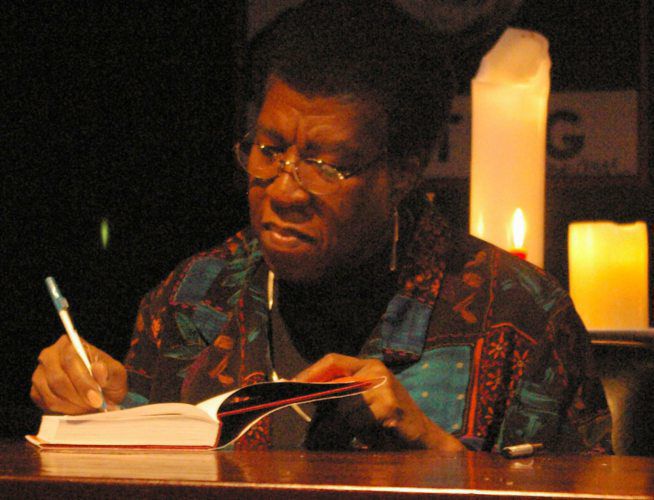

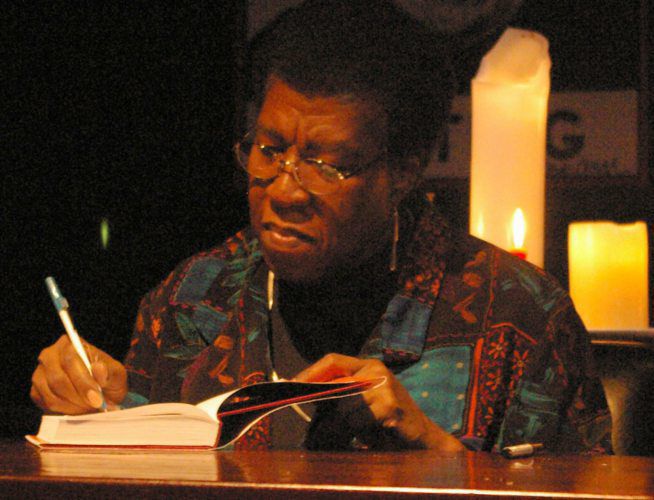

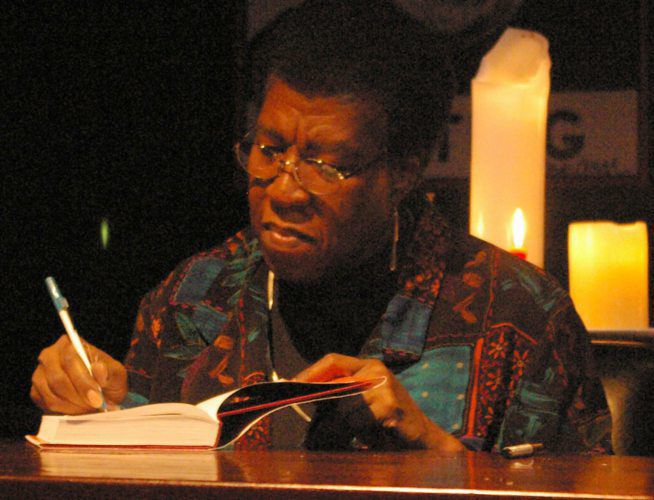

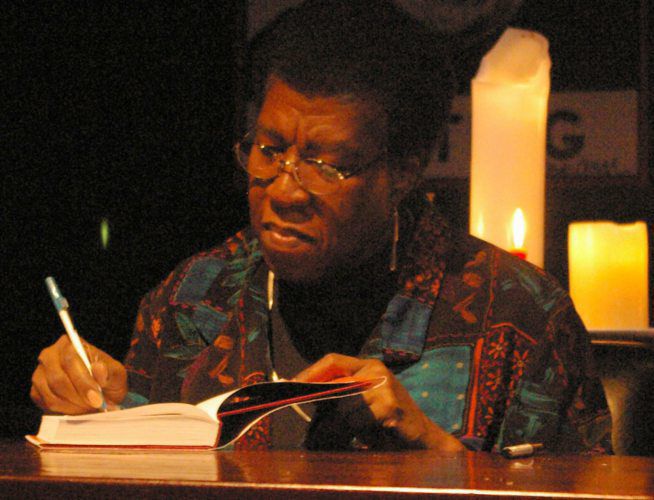

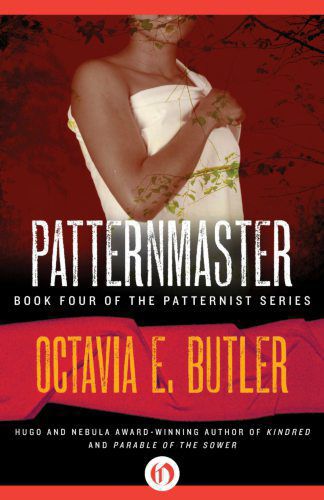

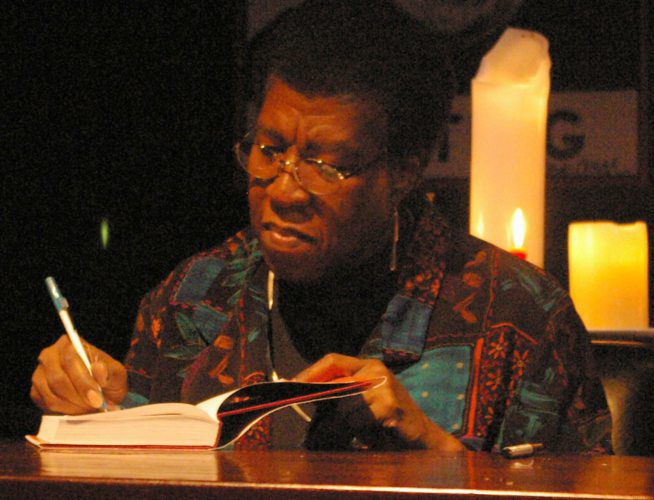

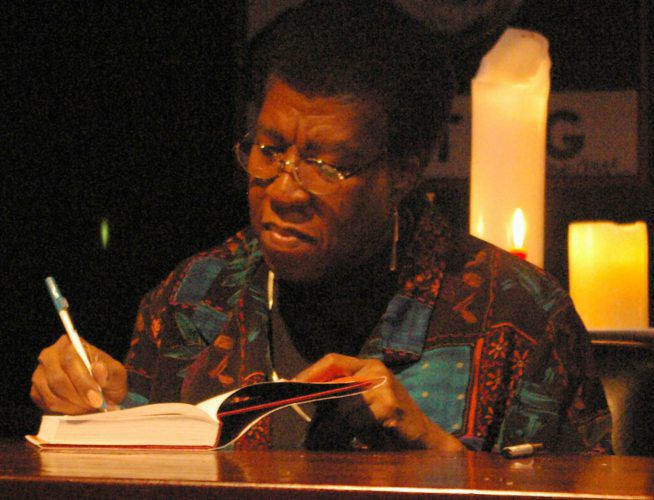

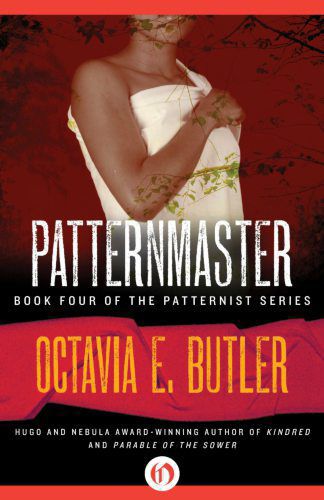

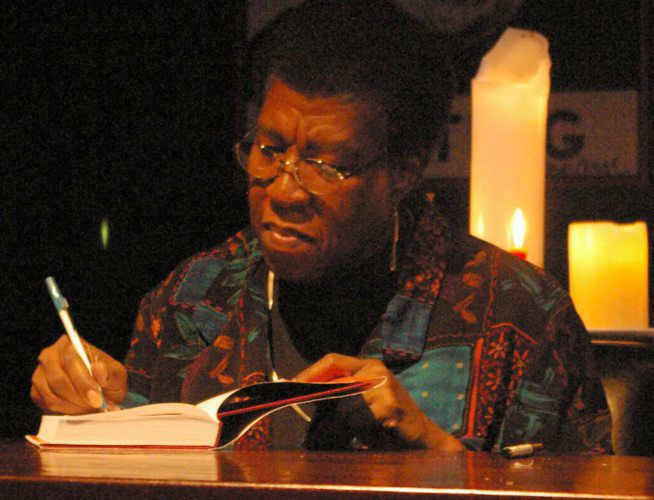

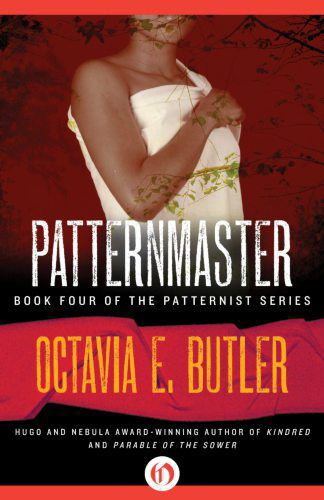

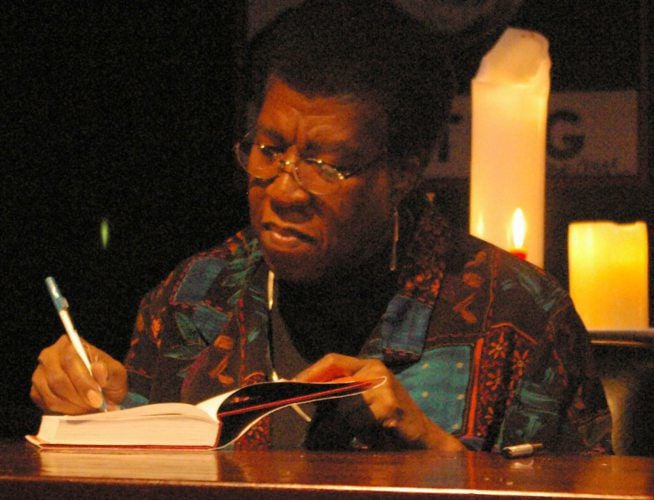

Octavia Butler (1947-2006)

One does not simply become the “grand dame of science fiction” … at least not when you’re Octavia Butler.

With Hugo, Nebula, Solstice and Locus awards to her credit, not to mention plaudits from the “Science Fiction Chronicle,” the Science Fiction Hall of Fame and the PEN American Center, Butler was a true force in her field.

And it’s more the shame her name isn’t spoken often enough in the same breath as Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury or Harlan Ellison (her mentor).

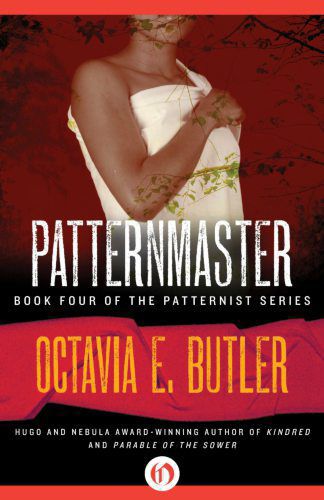

Her first published work, 1976’s “Patternmaster,” also was the first in her “The Patternist” series. But it was 1979’s “Kindred” that cemented her as an all-time great in science fiction. It’s a novel that covers topics like feminism, slavery and time travel. The book is taught in schools and discussed by critics to this day, 40 years later.

Sources: OctaviaButler.org, National Public Radio (tinyurl.com/qn8eegp).

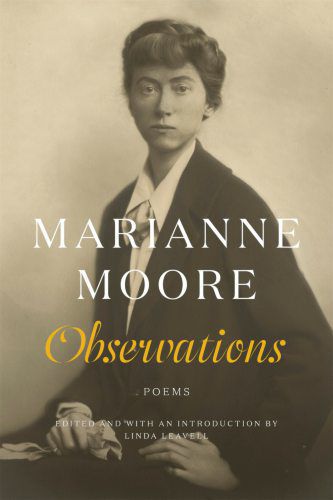

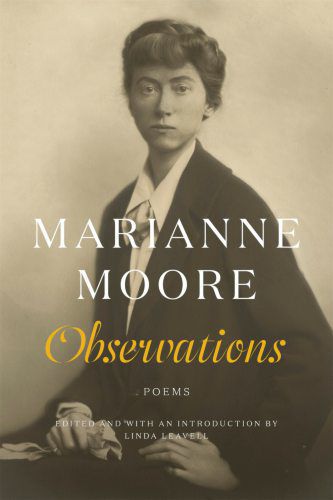

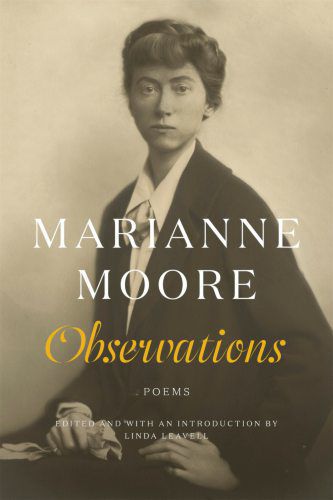

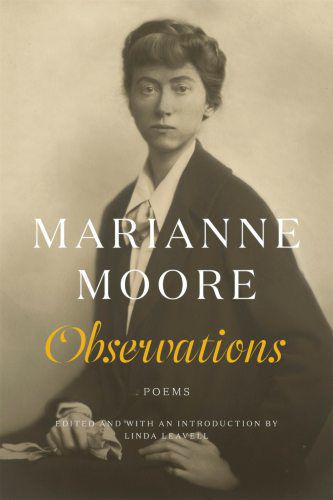

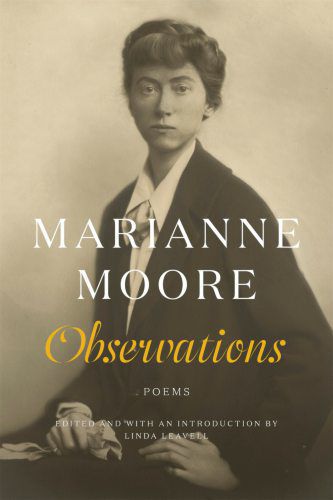

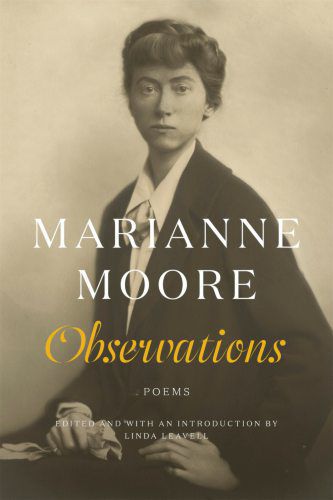

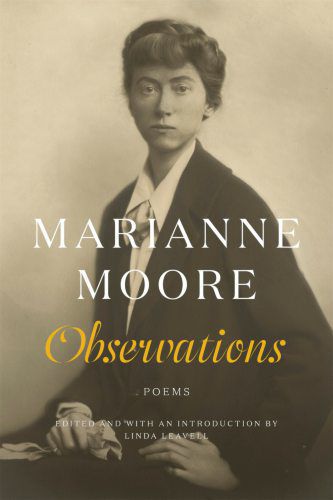

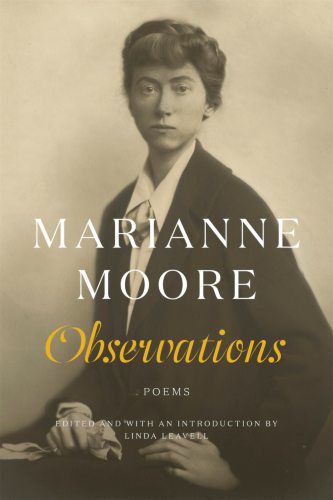

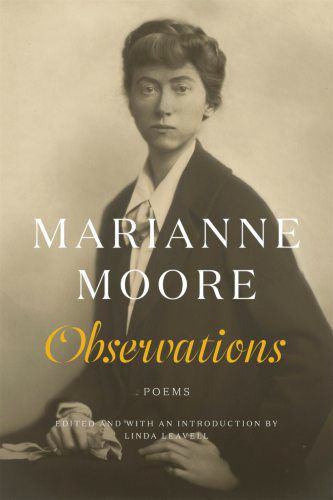

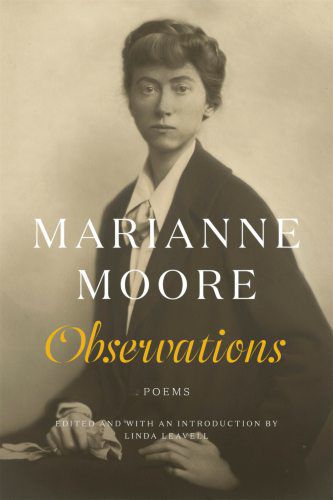

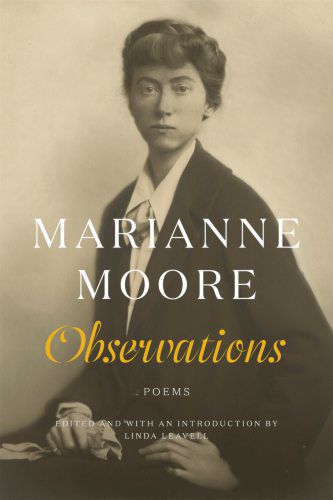

Marianne Moore (1887-1972)

No list of writers is complete without at least one poet, and Moore is a poet of no little renown.

Receiving a Pulitzer Prize in poetry, as well as a National Book Award and a Bollingen Prize, Moore was something of a celebrity in her time. Today, though, she’s best known among students of her craft.

Her work is at once both extremely experimental and hyper precise. Her poetry is famous for its ability to convey complex meanings and images with the least amount of words possible.

She also was known to court controversy, even among the poetic faithful. Her “The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore” (1976) heavily revised some of her earlier published work, in one case reducing a poem from 31 lines to three.

Sources: www.PoetryFoundation.org, Poets.org.

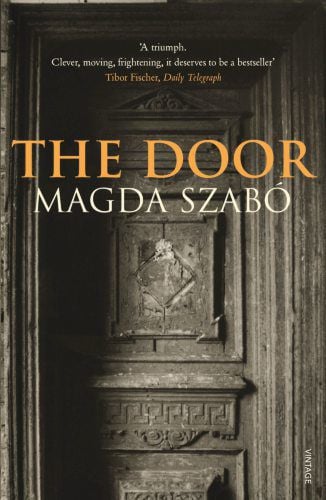

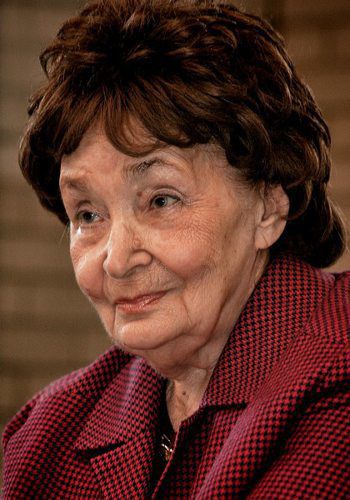

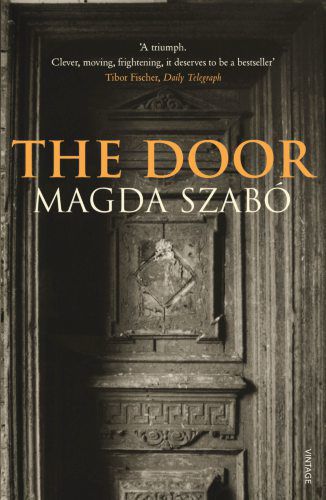

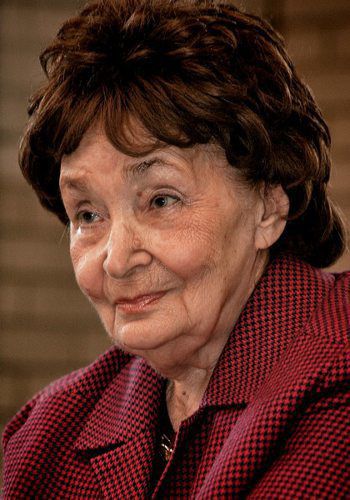

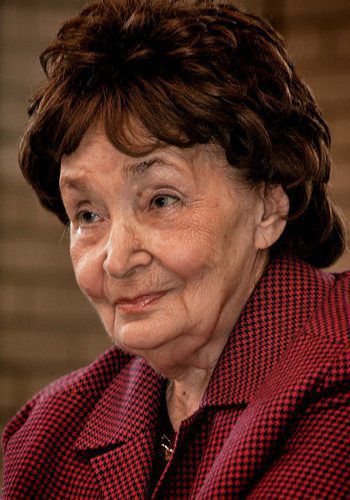

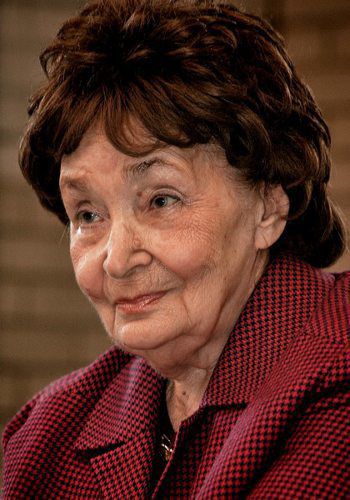

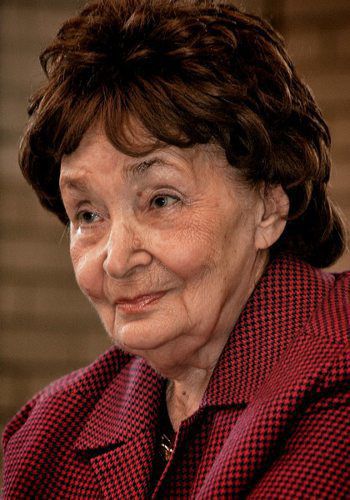

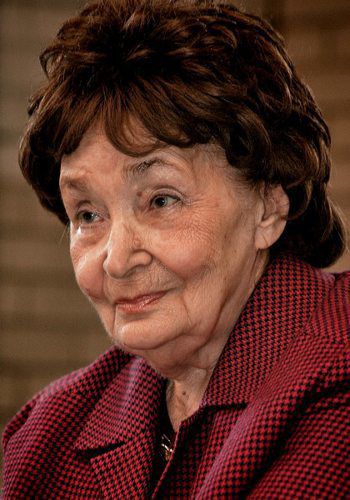

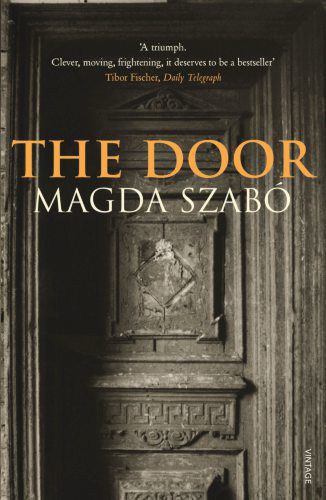

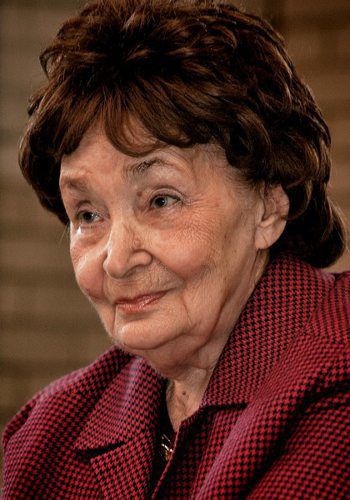

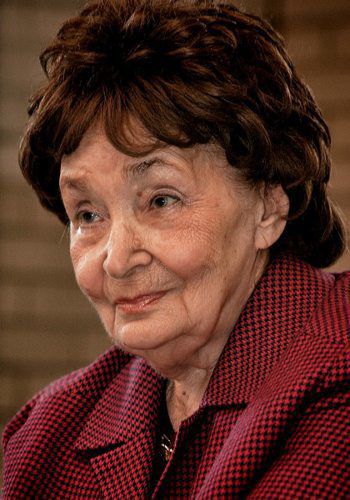

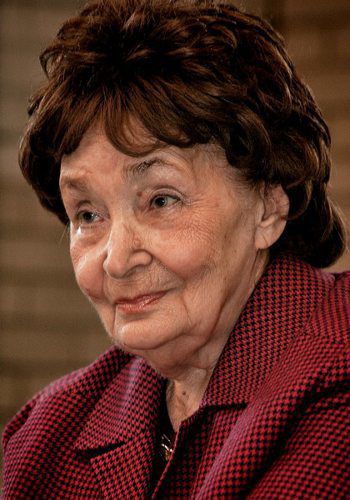

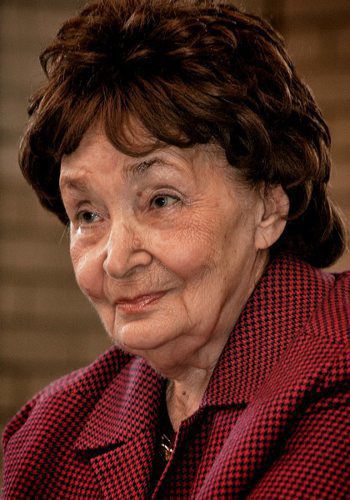

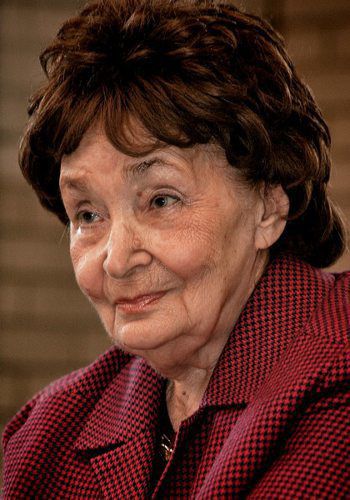

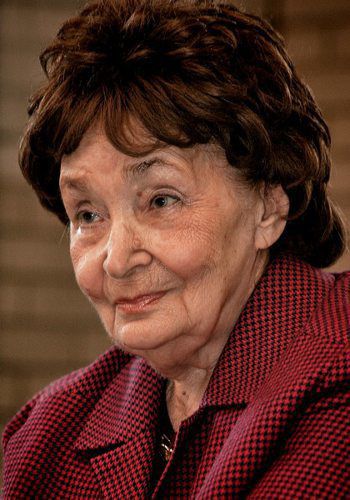

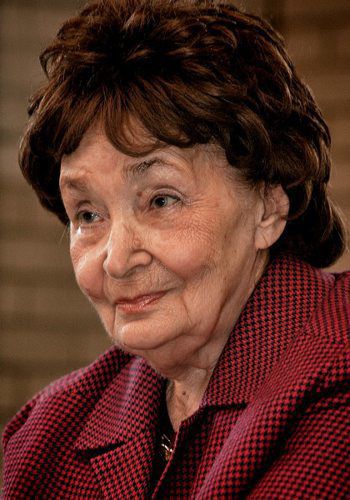

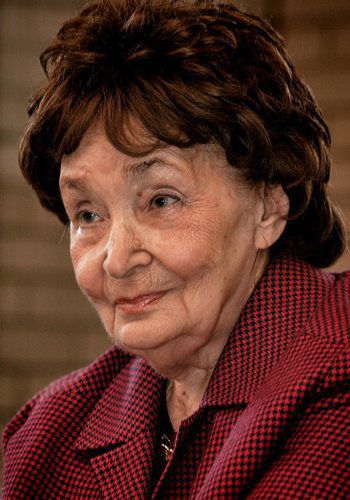

Magda Szabó (1917-2007)

Where the prior two women on this list have or had some amount of notoriety — and therefore could be considered not-so-hidden gems — Szabó is another story. And, that’s probably because most of her work was never published in English, especially during her lifetime.

Luckily for bibliophiles and Hungariophiles, that injustice is being rectified.

Considered one of Hungary’s best known authors, Szabó lived through the Stalinist rule of her home country (1949-1956) during which she was declared an enemy of the people and not allowed to publish.

Following the end of the blacklisting, her work has slowly disseminated to the rest of the world, with “The Door” (1987), and its two English translations being best known. Don’t let that stop you from exploring further, though, as her work is far more available today.

Sources: The New Yorker, GoodReads.com.

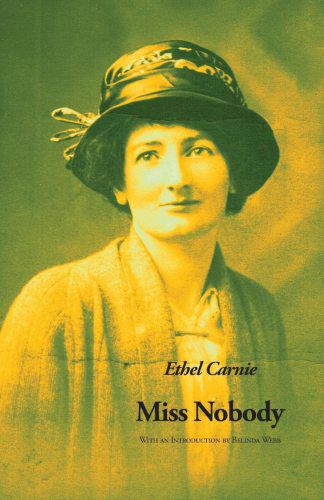

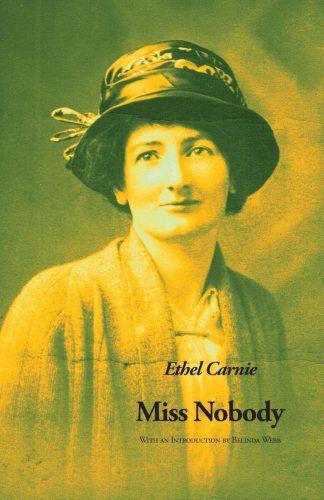

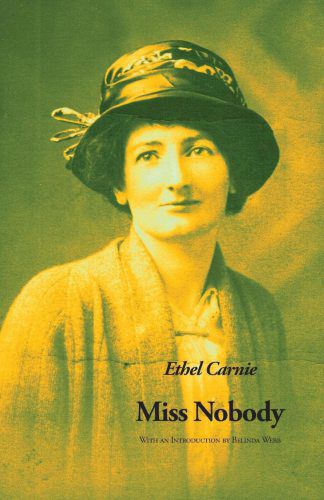

Ethel Carnie Holdsworth (1886-1962)

Peeking in to the life of working woman isn’t something terribly outre in 2020. But when working woman and feminist author Holdsworth started writing about her life in the factory in the very early 20th century, it was something of a mini-revolution.

And did she ever have things to write about. She started working in a cotton mill part-time at 11, went full-time at 13 and didn’t leave the life of “a beggar and a slave” until 22. Encouraged to do so by a journalist who interviewed her, she left for London and a full-time career of the written word.

And even that had its ups and downs.

Not allowing herself to be confined to a single medium, she plied her craft as a journalist, poet, children’s author and editor.

Her work begins with “Rhymes from the Factory” (1907) and includes the children’s story “The Blind Prince” (1913) and the best-selling in its time “Helen of Four Gates” (1917), which was adapted into a silent film.

Sources: CottonTown.org, Project Muse (muse.jhu.edu).

Margery Sharp (1905-1991)

While you’ve probably heard of the Disney films “The Rescuers” (1977) and “The Rescuers Down Under” (1990), did you know they are adaptations of Sharp’s work?

Before turning her attention to children’s literature, Sharp published 15 novels. She also was a mainstay contributor to magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping.

Her writing is noted for its charm and ability to build complex characters that might have turned into one-note stereotypes in the hands of other writers.

It wasn’t just her children’s fiction that got the big screen treatment. “Cluny Brown,” starring Charles Boyer and Jennifer Jones in the titular, role hit theaters in 1946. Her novel, “The Nutmeg Tree” became “Julia Misbehaves” in 1948. And “Britannia Mews,” featuring Dana Andrews and Maureen O’Hara, was released in 1949.

Sources: www.LiteraryLadiesGuide.com, New York Review Books, Early Bird Books.

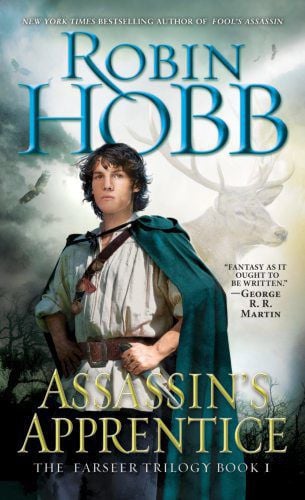

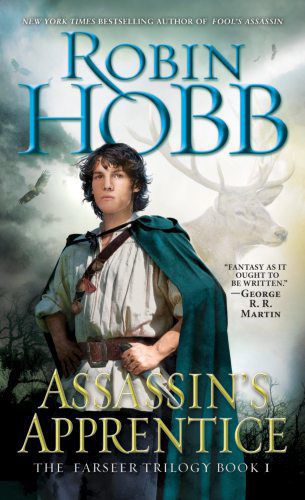

Robin Hobb (1952-)

While this list has science fiction covered with Octavia Butler, that leaves the others in the “big three” of genre fiction in need of attention.

Hobb — who sometimes goes by her other pen name, Megan Lindhold — ably fills out the fantasy portion, and stay tuned for horror.

No rundown of Hobb’s work would be complete without first looking at her “Elderlings” series, which began with her first novel, “Assassin’s Apprentice” (1995) and continues through the most recent entry, “Assassin’s Fate” (2017).

The series is organized in a somewhat unique way in that the books all are part of a single chronological world and series of events, but they’re subdivided into four trilogies and one quadrilogy. The subdivisions are written in a variety of styles, tones and settings.

And that’s just one series.

If you need any more convincing, her work often is mentioned in the same breath as George R.R. Martin, Terry Brooks and Tad Williams.

Sources: Reedsy.com, RobbinHobb.com, Den of Geek.

Helen Oyeyemi (1984-)

By far the newest pen on this list, that doesn’t mean Oyeyemi is any less worth your attention.

Especially if you’re a fan of horror fiction.

But Oyeyemi doesn’t neatly fit into the most well known horror subgenres like slashers, supernatural or cosmic. Instead, her writing is shaped around the telling of dark, disturbing fairy tales.

And she got her start early. Her first novel, “The Icarus Girl” (2005) was written while she was in high school and published when she was 20.

Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria, raised in South London and has lived in Berlin, Paris, Budapest and Prague.

In the process of writing her stories — which, incidentally, share a lot in common with the themes and feel of many fairy tales in their original forms — she mixes together a heady concoction of fear, allegory, unique characters and a (sometimes terrible) sense of place.

Sources: National Public Radio (tinyurl.com/r9oul87), Vox.com, www.PanMacMillan.com, HelenOyeyemi.com, The Guardian.

Anthony Frenzel writes for the Telegraph Herald.