When it comes to household duties such as changing diapers, handling chores and meals and managing family schedules and activities, many couples who don’t have children expect that they will more or less share the work equally should they have kids one day.

The reality is not quite so rosy — at least for mothers.

A new poll from the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that although women generally expect to do more in their household, Americans without children remain more optimistic that they would share responsibilities equally with a partner compared with what parents report happens. That’s true even when factors such as the age of respondents are taken into account.

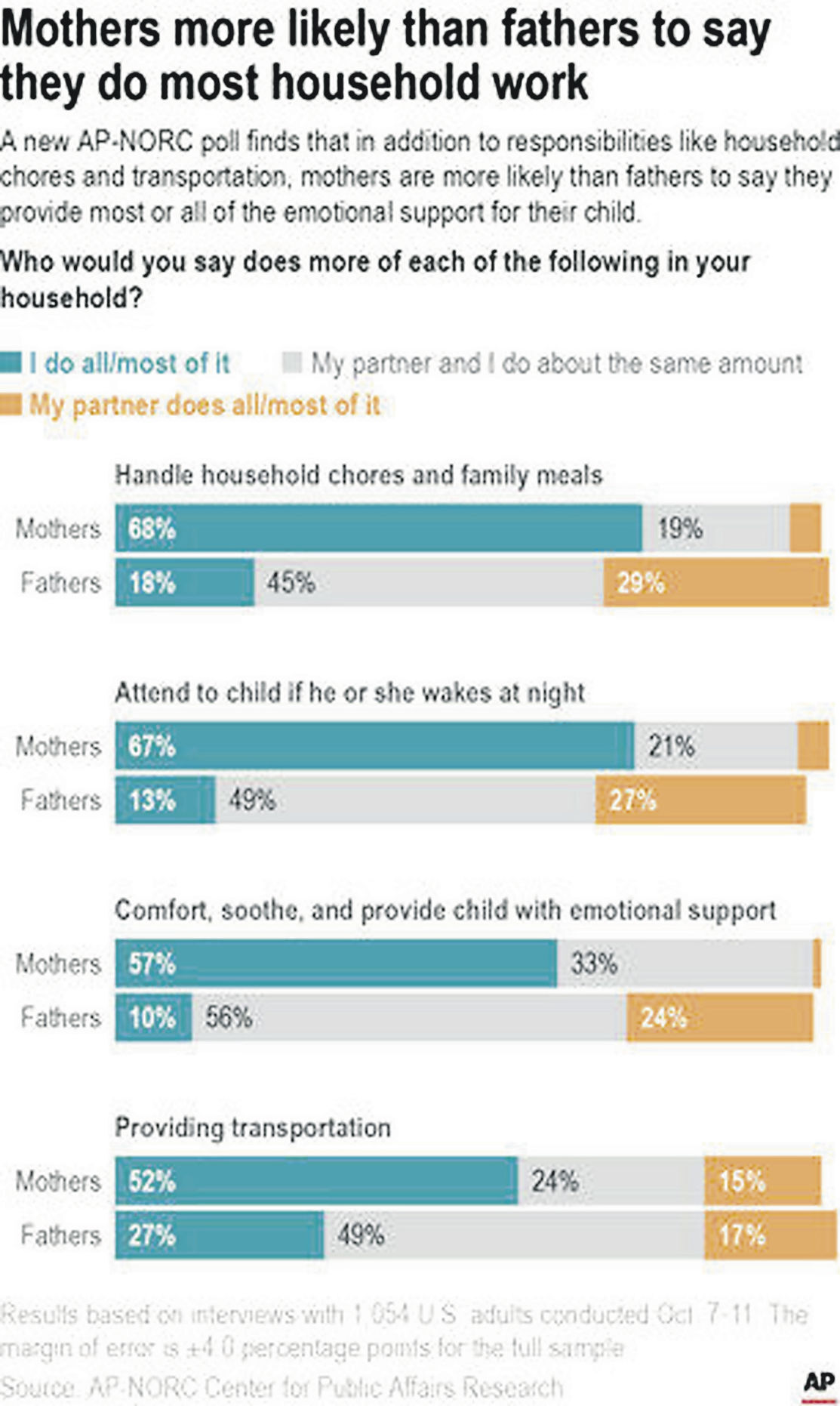

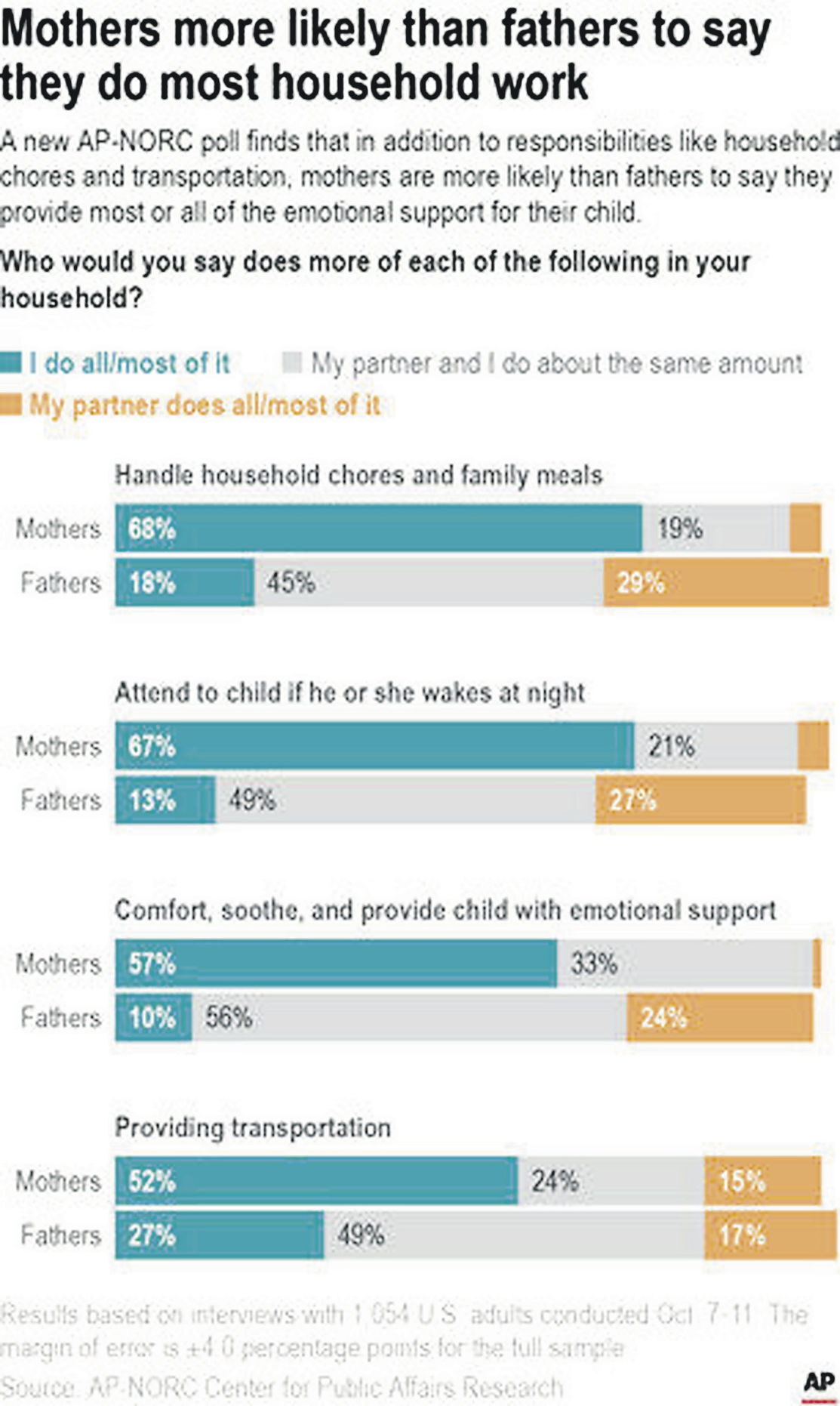

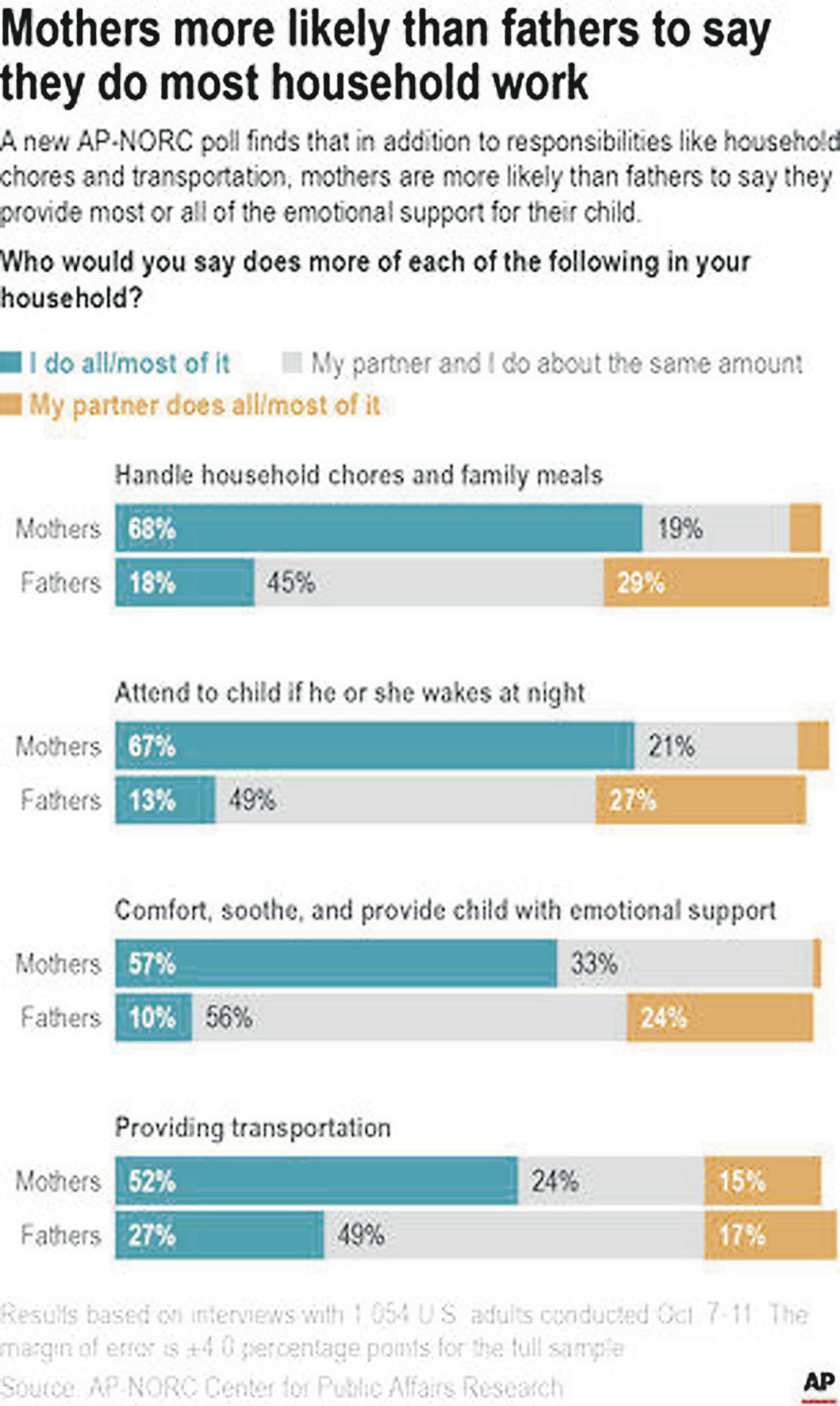

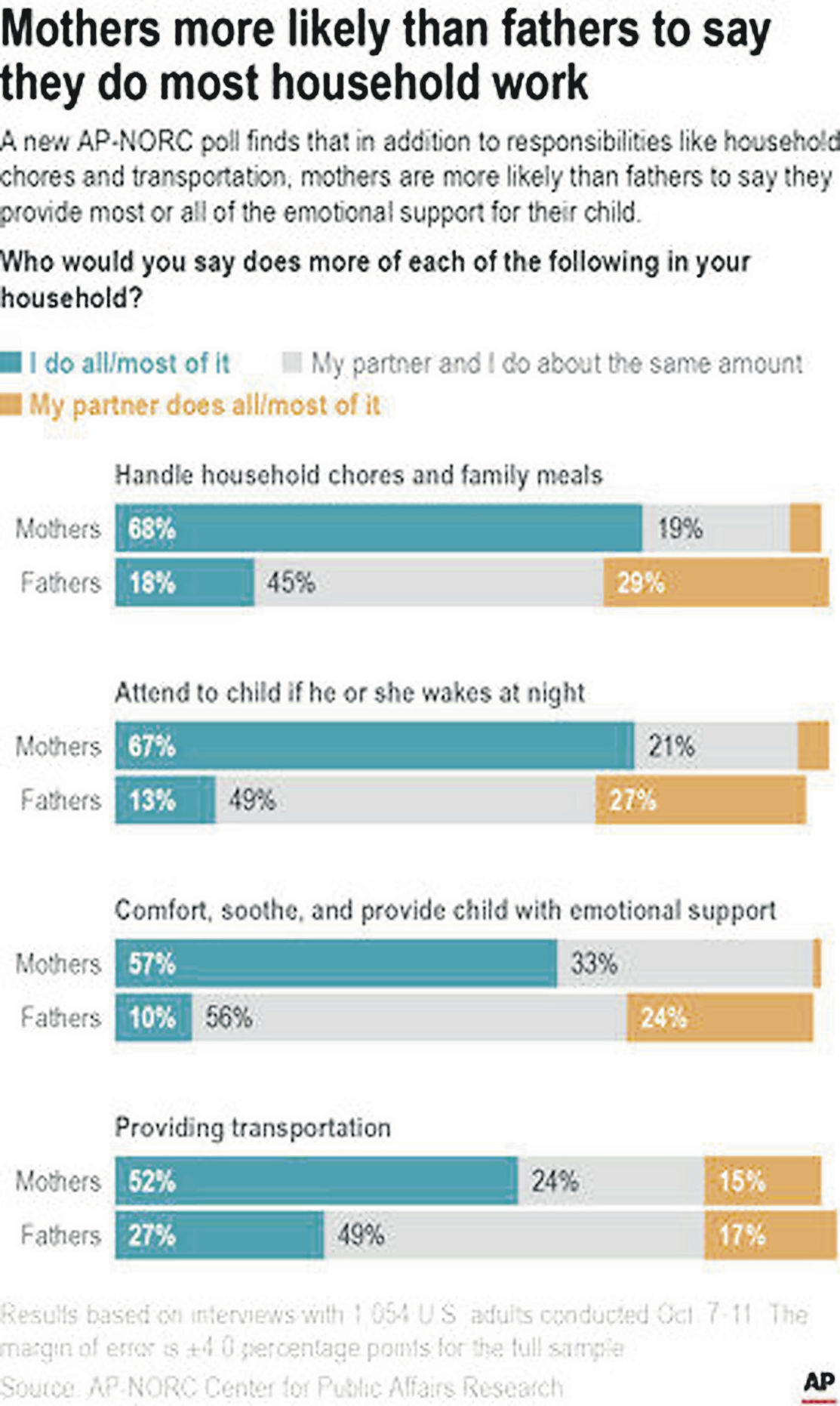

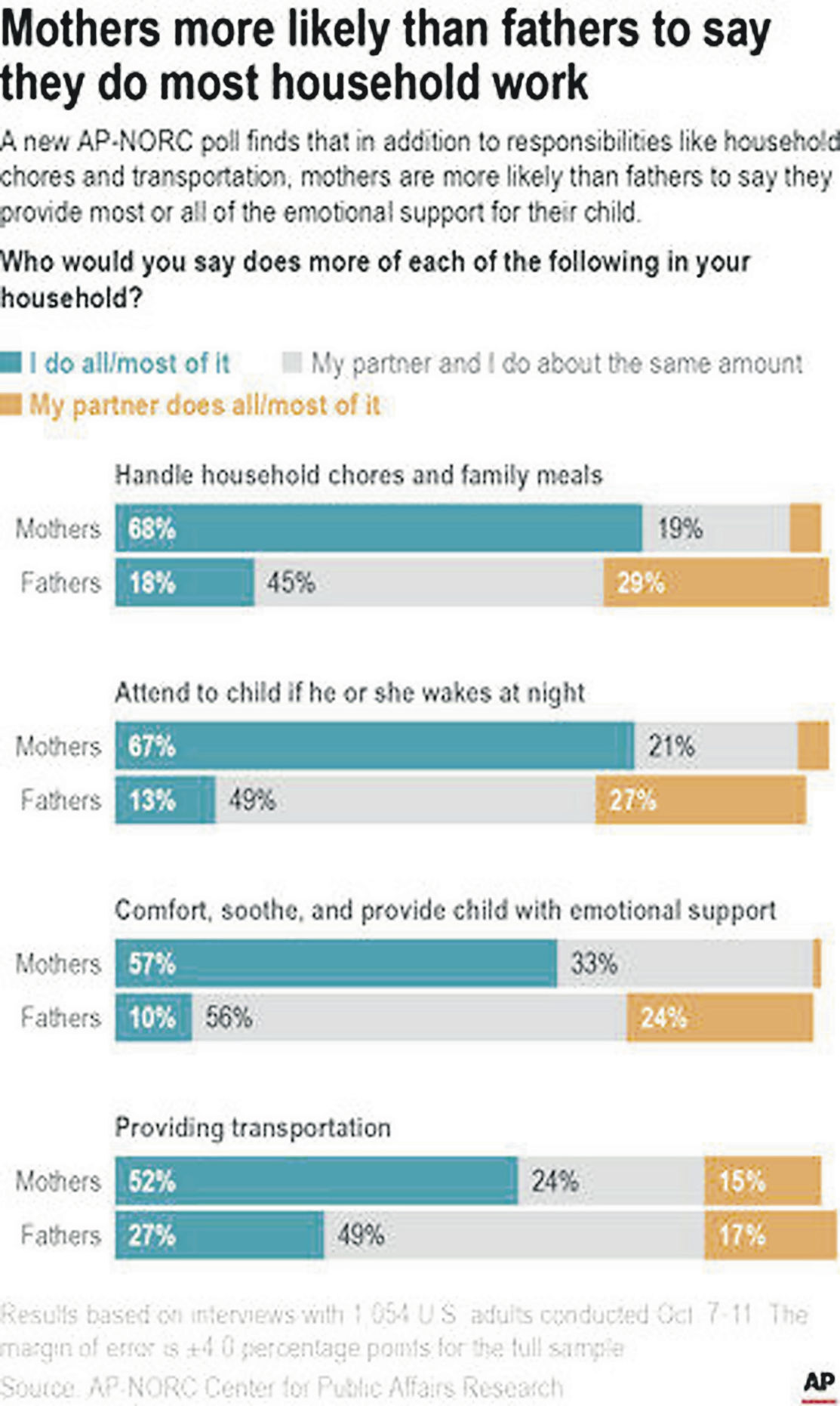

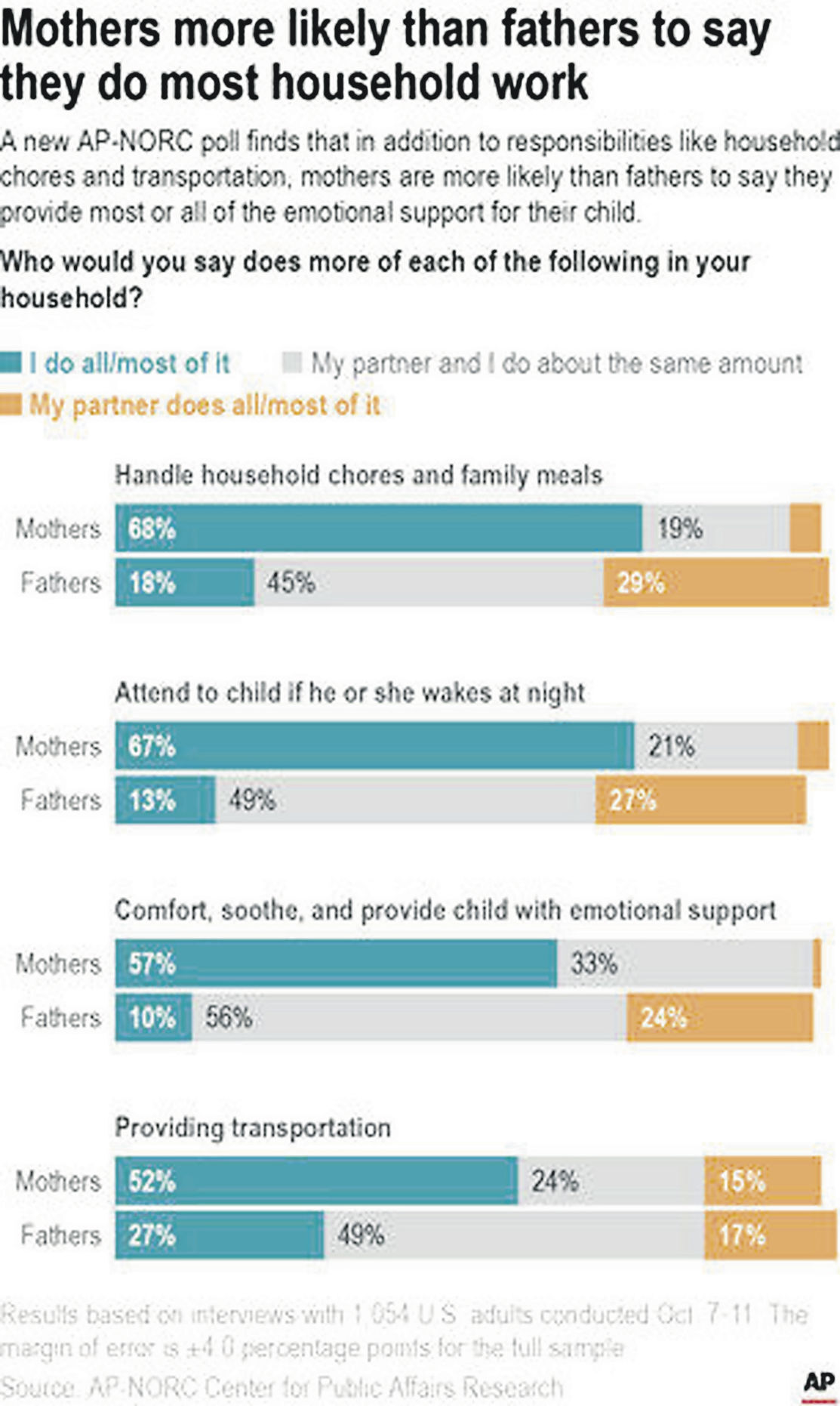

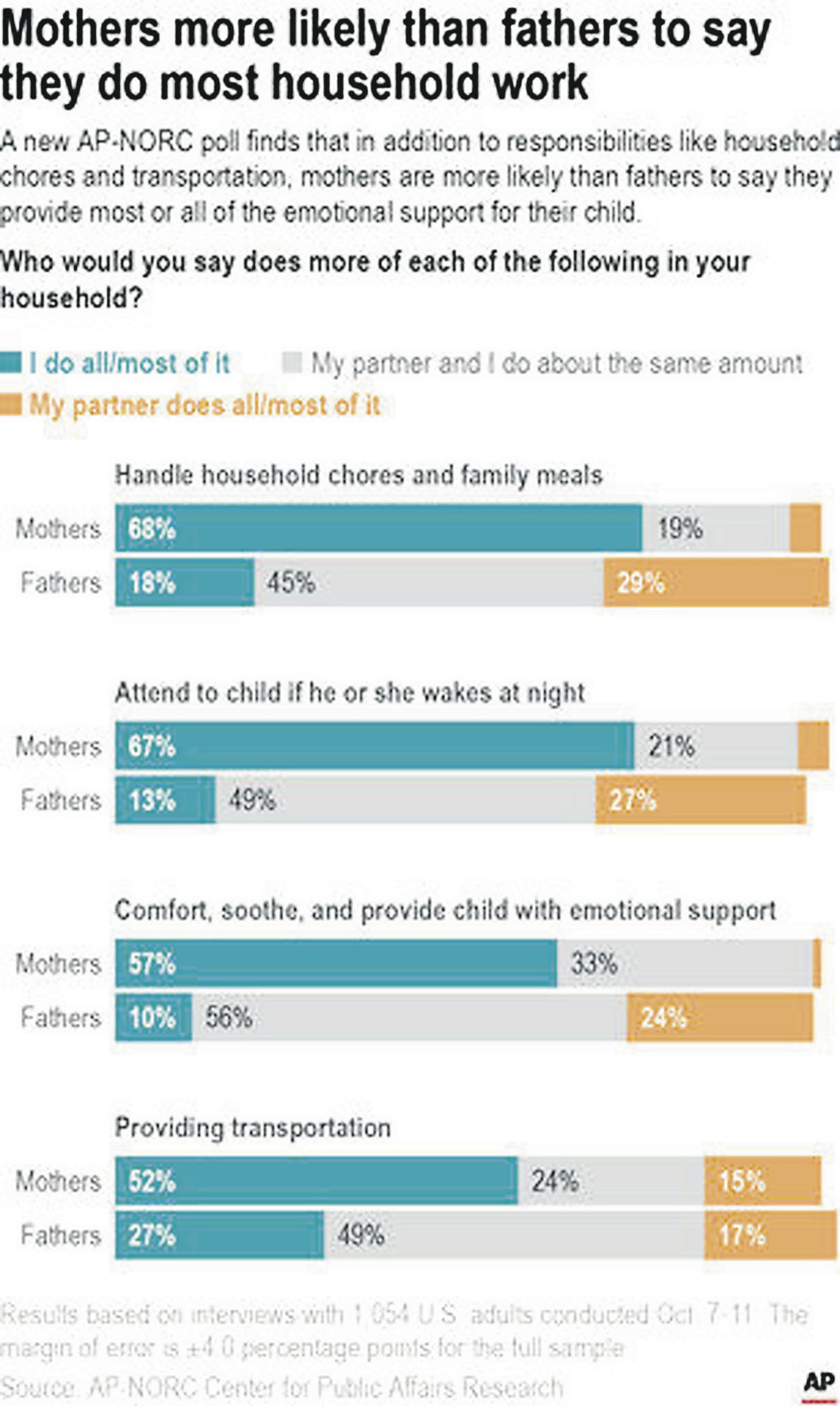

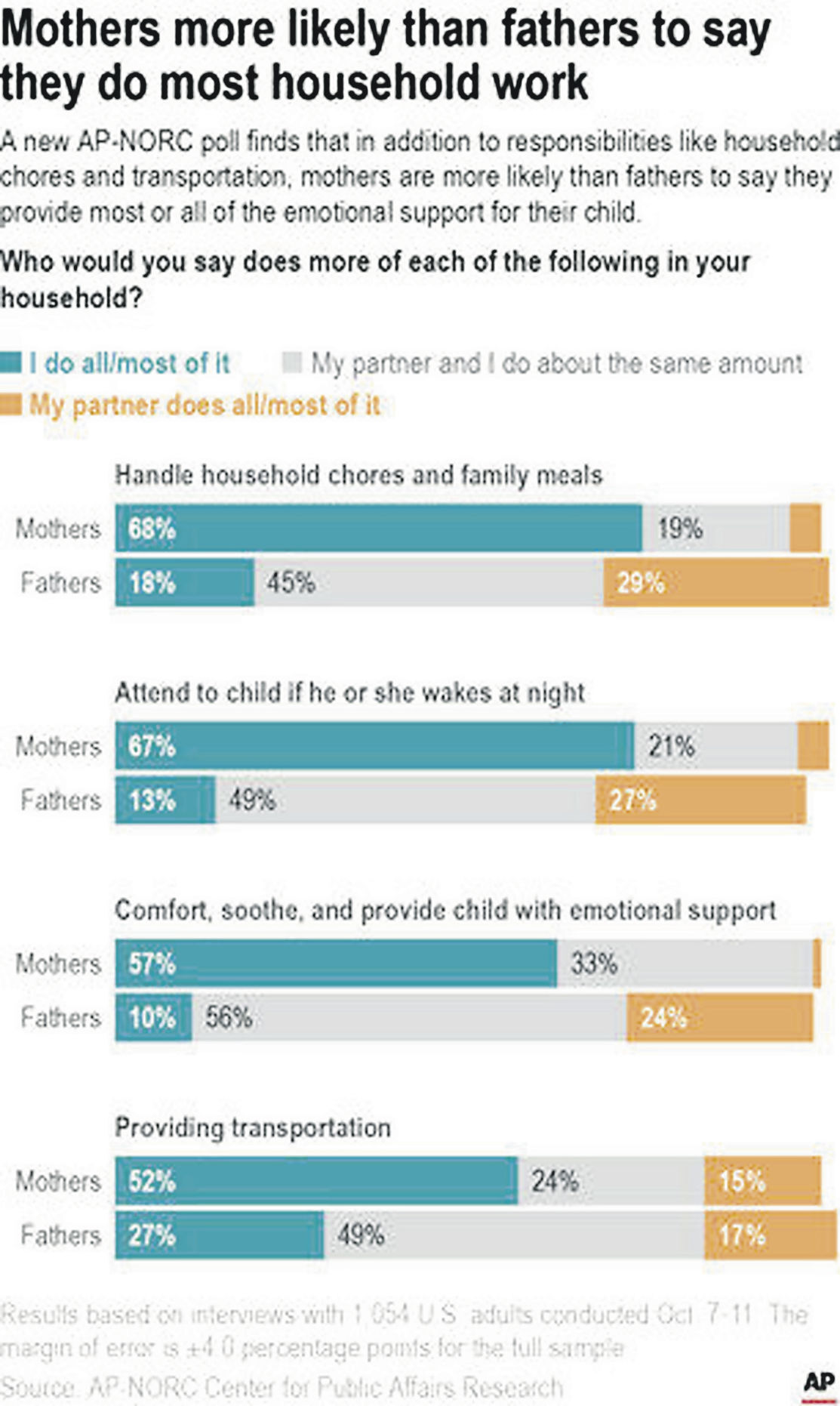

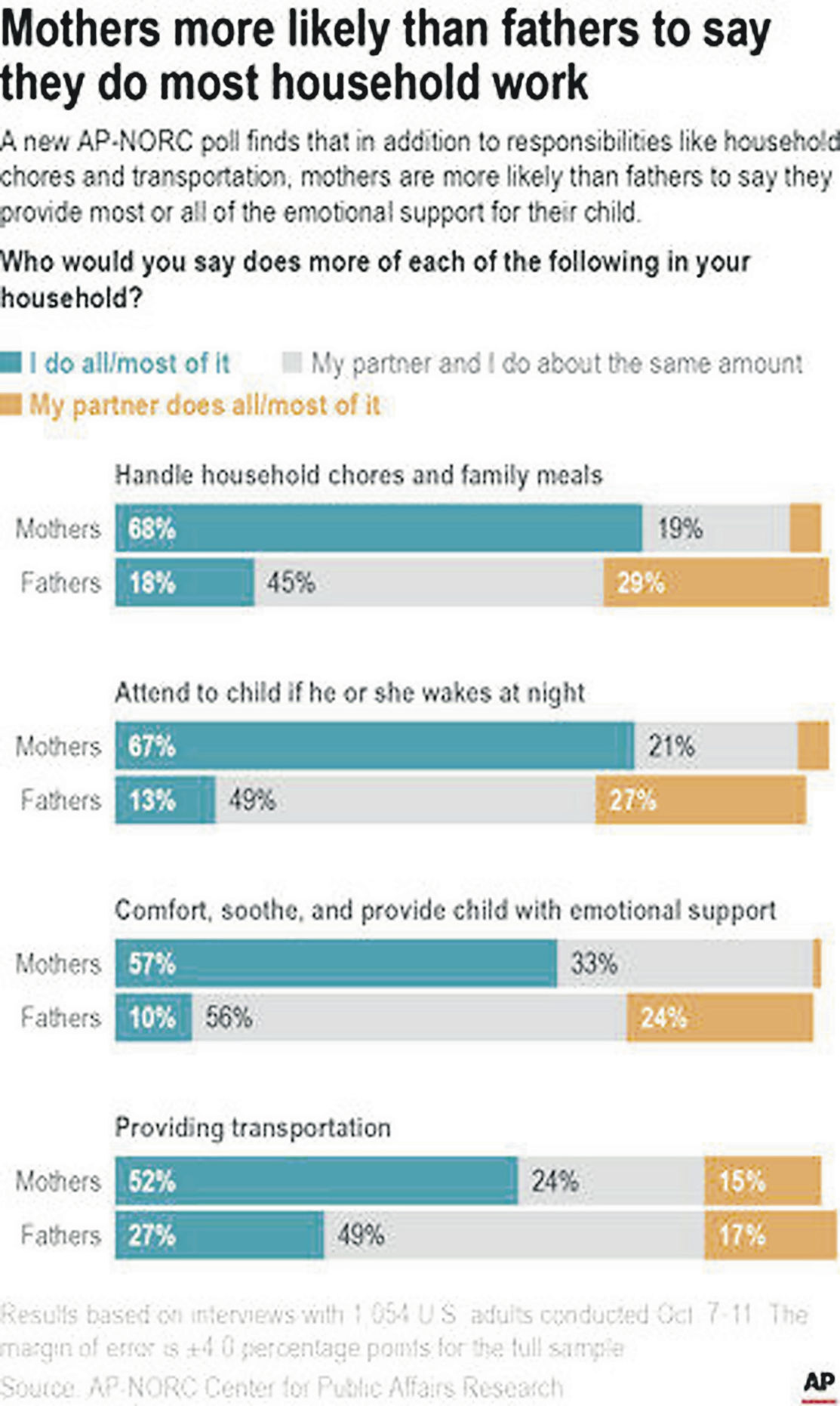

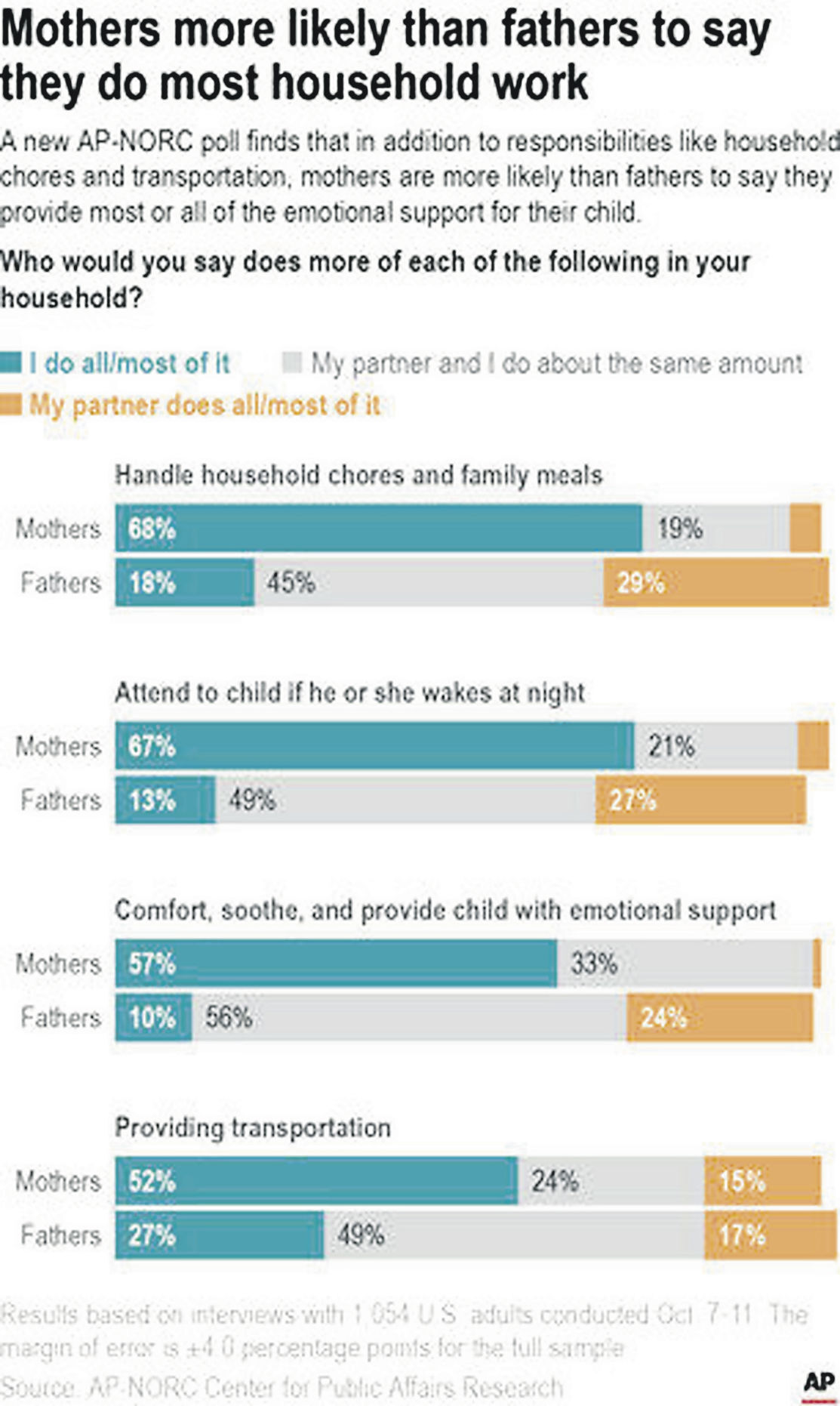

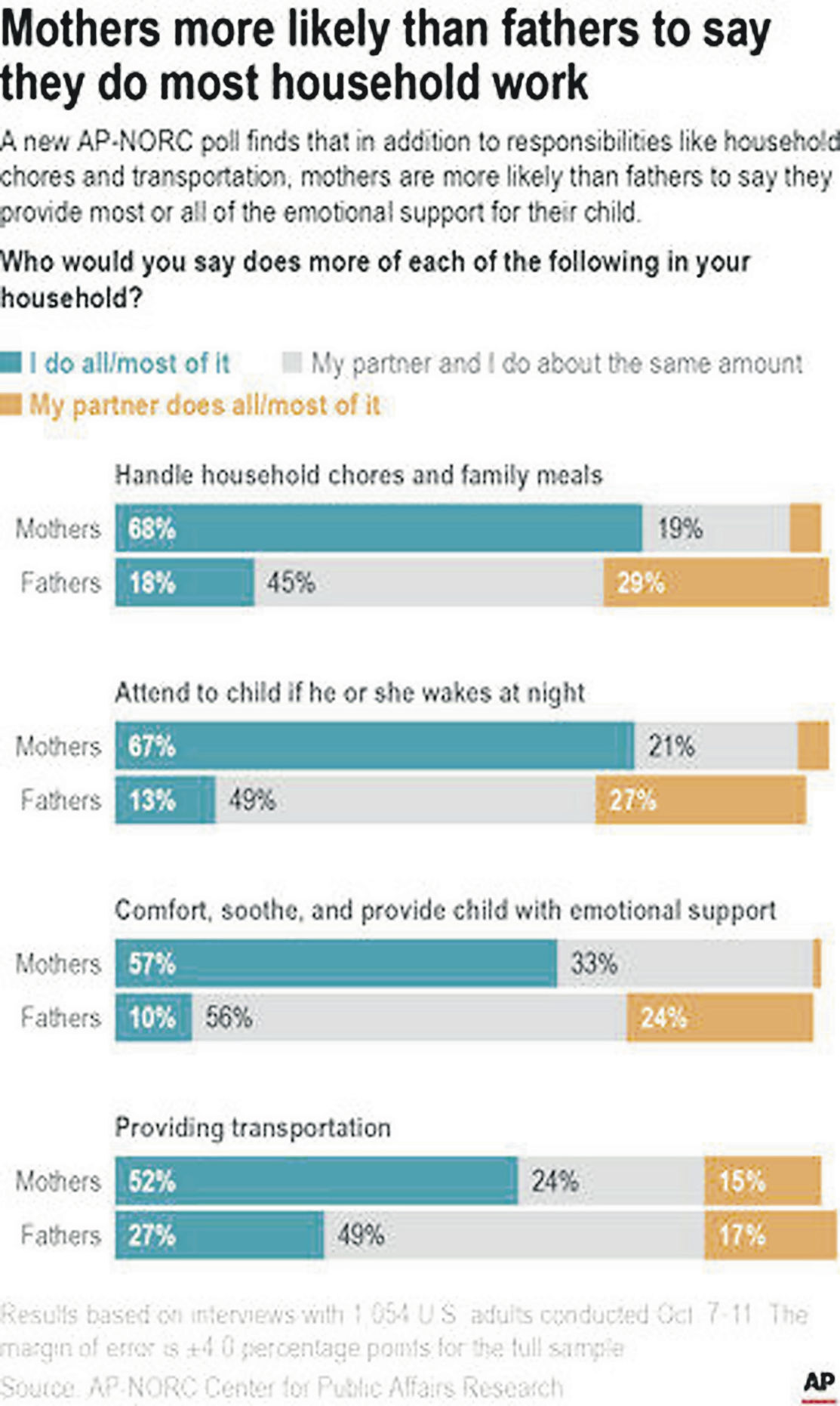

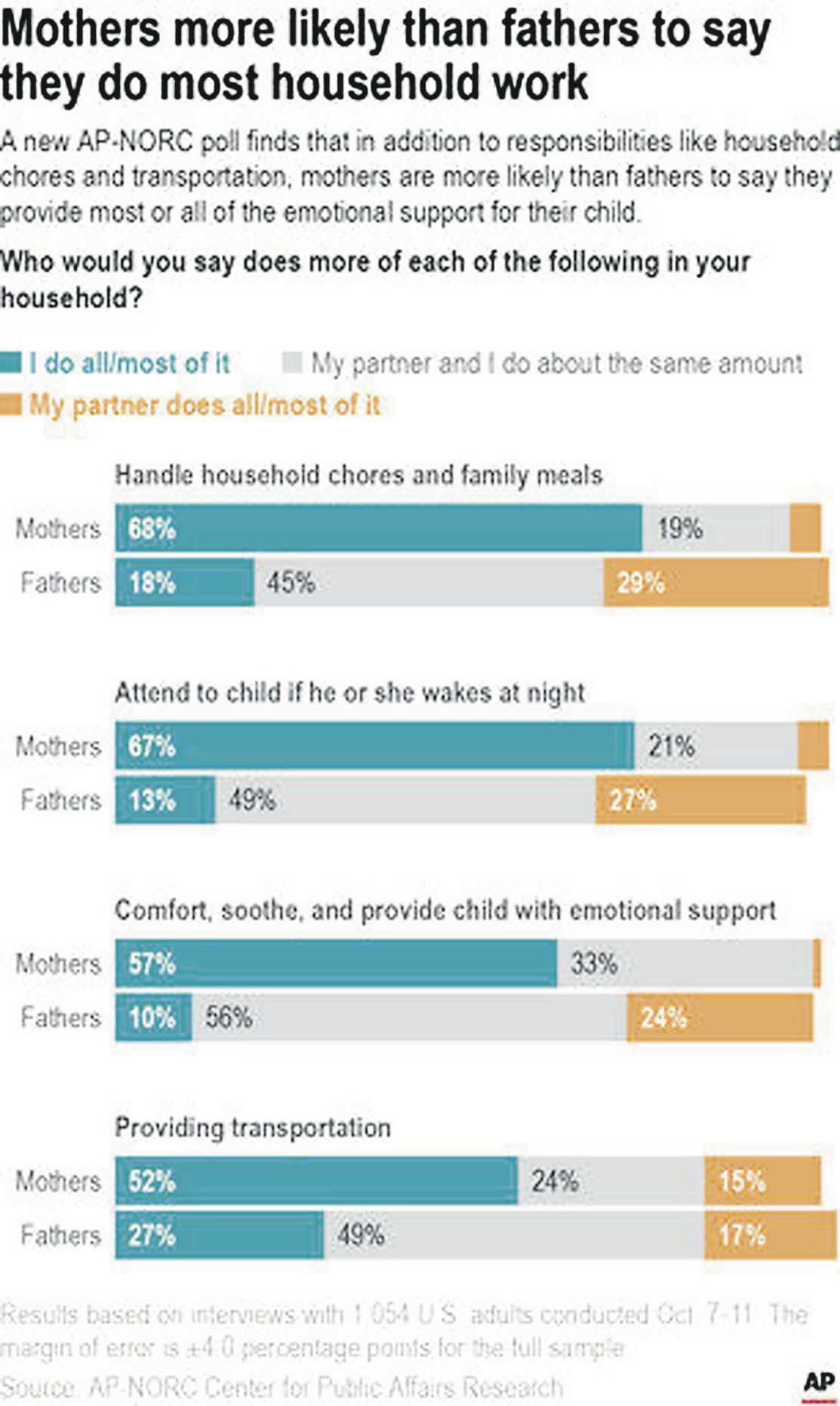

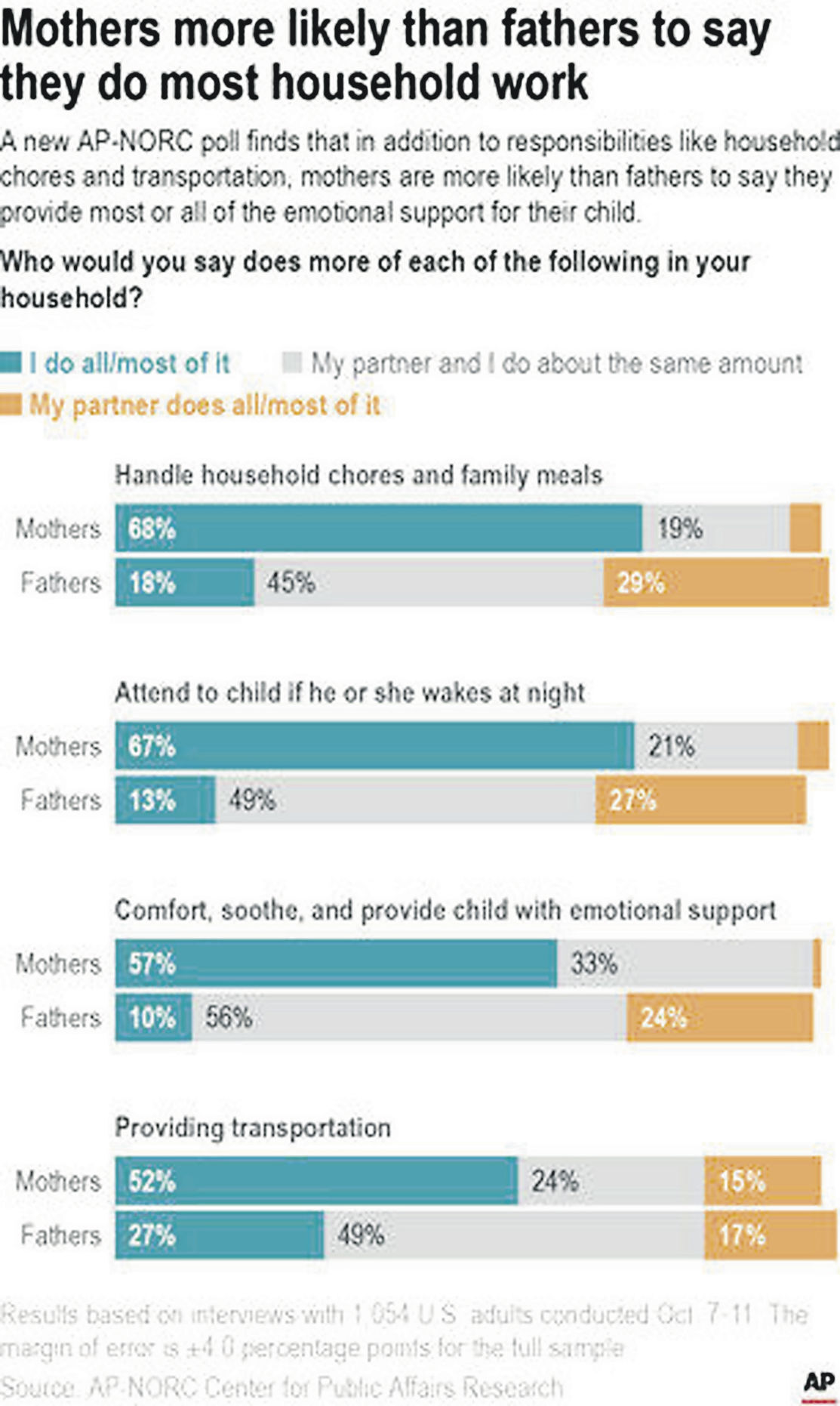

The poll asked about eight specified household responsibilities and found that 35% of mothers report doing more than their partner for all eight, compared with just 3% of fathers who report the same. For instance, about half of mothers said they are completely or mostly responsible for providing transportation to their kids, while only about a quarter of fathers said they are responsible for all or most of it.

By contrast, majorities of both men and women who are not parents said that if they did have kids they’d share equally in things like providing transportation, changing diapers and attending to children waking up at night.

Mothers and fathers had different ideas about who does the bulk of household chores. For instance, 21% of mothers said they and their partner equally attend to children if they wake up at night, while 49% of fathers said the same thing. So who is right?

“When you look at time use data, women are more correct than men,” said Yana Gallen, assistant professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, who worked on the poll.

Life also can complicate the best-laid plans. Liana Price, 35, who has a 4-month-old baby who came as a “very much wanted surprise” during the height of the coronavirus pandemic when Price was undergoing chemotherapy treatments on her hands and had a pregnancy complication, said she stopped working in January as a result of everything going on.

“Things just kind of changed very drastically. And suddenly for us, we didn’t really have like a plan,” Price said. While Price and her husband had planned to both work full time, with her taking maternity leave offered by her job as a registered nurse, instead she quit her job and they began to run through savings.

She says she and her husband divide child care equally — including attending to night wakings.

“When I was breastfeeding, there was no point in him getting up in the middle of the night. But now that I’m formula feeding, we alternate nights,” she said. “However, during the day my husband does work from home. He travels, too. So when he travels, obviously everything is on me.”

Experts say one reason women report doing more house and child care work is not only because they do more — which often is true — but also because men are not always aware of all the work involved. That includes planning family activities and organizing appointments and even things like providing children with emotional support.

The poll found that 57% of mothers said they provide “all or most” emotional support to their children. Only 1% of mothers said that their partner does. In contrast, 10% of fathers said they are the primary provider of emotional support to their kids, while 24% said it’s their partner.

Much has been said about the effects of the pandemic on women, including many women who left or stepped back from the labor force to take care of their children or aging parents. The U.S. lost tens of millions of jobs when states began shuttering huge swaths of the economy after COVID-19 erupted. But as the economy has quickly rebounded and employers have posted record-high job openings, many women have delayed a return to the workplace, willingly or otherwise.

In the spring of 2020, roughly 3.5 million mothers with school-age children either lost jobs, took leaves of absence or left the labor market altogether, according to an analysis by the Census Bureau. Many have not returned. A recent report by the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. found that one in three women over the past year had thought about leaving their jobs or “downshifting” their careers. Early in the pandemic, by contrast, the study’s authors said, just one in four women had considered leaving.

“But another thing that happened during the pandemic is a lot more jobs became remote and working from home became OK with a lot of jobs,” Gallen said. “So I think that actually really helps women in the workplace because a potentially big problem has been that, women don’t feel like they can take some of the higher-paying jobs available” that involve travel or long hours away from home.

“So this pandemic kind of moved forward a shift to more female friendly conditions and many jobs,” she said.

This includes schedule flexibility and, for jobs in which that’s possible, remote work. Women are more likely than men to say flexibility at work is important when thinking about whether or not to have a child, 74% versus 66%, according to the poll.

It’s not just the division of household responsibilities that having kids can throw into a loop. It’s been well documented that having children can hinder women’s careers, both when it comes to pay when compared with men (including men with children) and advancing to better jobs.

According to the poll, 47% of women say having a child is an obstacle for job security at their current or most recent job, compared with 36% of men. Americans younger than 30 were especially likely to say that, compared with older adults.

Amy Hill, who is 31 and lives in West Virginia, said she’s happy with her home division of labor, even though she does more than her husband. That’s because he works in the coal mines, doing 16-hour shifts away from home. Her work, while steady, is not full time — she does makeup for proms, weddings and other events.

“I think it helps not being around each other a whole lot because I miss him when he’s gone, you know?” she said. “As long as we’ve been together, he’s been working underground. And also, he doesn’t really fold the towels the way I want them to be folded.”

The AP-NORC poll of 1,054 adults was conducted Oct. 7-11 using a sample drawn from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is plus or minus 4 percentage points.

Barbara Ortutay writes for The Associated Press.