Jennifer Thompson was in college when she came face to face with every woman’s worst nightmare.

Held at knife point by an intruder who broke into her apartment while she slept, she was brutally raped. And though she was able to escape, the physical and psychological damage would have a rippling effect.

“Since 1984, the majority of my life has been this story,” Thompson told the Telegraph Herald in a phone interview. “Sometimes I look at myself and wonder how I’m a survivor.”

Steps toward healing began when Thompson (a Caucasian woman) identified Ronald Cotton (an African American man) as her attacker from a police lineup. But there was one major catch: Cotton was innocent.

A DNA test would later reveal the truth. But that came 11 years after Cotton was put behind bars for the crime he didn’t commit.

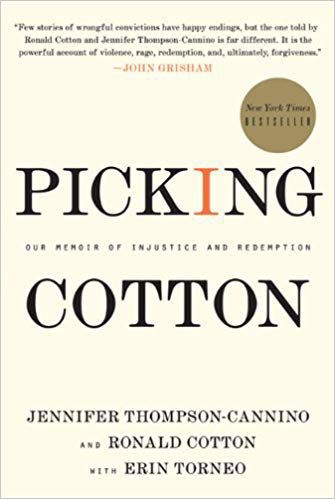

Two years after being exonerated, Thompson summoned the courage to reach out to Cotton. What ensued was an unlikely friendship that became the basis of a 2009 book they co-authored titled, “Picking Cotton.”

Selected as Carnegie-Stout Public Library’s inaugural All Community Reads, beginning on Monday, Sept. 30, approximately 4,500 copies of the book will be available for free from various locations throughout the area, thanks to funding from the Dubuque Racing Association.

It will culminate in a presentation by Thompson and Cotton at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 5, at Five Flags Theater in Dubuque.

“I read this book nearly 10 years ago, and it had a powerful impact on me,” said Susan Henricks, library director at Carnegie-Stout. “I hoped then that one day I could invite the authors to Dubuque.”

A new initiative from Carnegie-Stout, All Community Reads aims to tackle restorative justice and open discussion about the topic on a community-wide level.

“A library member, Kathleen Weber, met with me and asked me if I had ever considered a program on restorative justice,” Henricks said. “We talked about a couple of options, and I was following other leads, but nothing was coming together. At that point, a light bulb went off in my mind: Why not have an All Community Reads event on a major scale? And I knew just the book.”

Henricks described restorative justice as an opportunity for the victim and offender to meet to discuss the crime, the impact it had on their lives and what should be done to repair the harm. Often the meetings will include more than the victim and offender, with all affected by the crime in attendance. And it may or may not involve the criminal justice system.

“This book is an example of two people meeting to discuss what took place and the impact on their lives,” Henricks said. “On a practical level, it is highly accessible and a page-turner. On a different level, it is a profound story, and you cannot help but identify with both Thompson and Cotton. The result of the story for both was forgiveness and healing.”

Both were pivotal in Thompson’s recovery. And they couldn’t happen without she and Cotton connecting.

“I was stuck — stuck in a place of fear, anger and brokenness,” Thompson said before meeting Cotton. “I couldn’t live there anymore. I needed answers. And I needed to meet the person I didn’t know. It was the only way for me to move forward and not stay where I was, continuing to feel the way I felt. I needed to meet Ronald. And he deserved to meet me.”

During that first meeting, the two learned of how the experience broke them and their families. It compelled Thompson to continue “peeling back the layers.” Even now, she continues to work on addressing those broken places in her life, as well as rejecting blame. It’s all a part of living, Thompson said.

“The truth is that if we walk outside out homes and engage in life, we’re going to get hurt,” she said. “We’re going to be vulnerable. We’re going to be broken. And we’re going to have loss. But there is always a space to have forgiveness, to ask for forgiveness and reconcile.”

Having traveled throughout the country to discuss the book, along with Cotton, Thompson said she has seen many reactions.

“I find that on one hand, it addresses the flaws in our justice system,” she said. “You take someone who has suffered a trauma, like myself, and within days, you are asked to help solve a crime that occurred to your personal body. Your memory is contaminated in that time, and you don’t even know it. In my case, I was asked to identify a suspect who wasn’t in the lineup. As the victim, you never want the wrong person to go to jail. You want the right person. The system in place didn’t just fail me and Ronald, it failed the community. There was still this individual out there, allowed to continue doing harm to others. And it took that individual causing harm to set this whole thing in motion.”

On the other hand, Thompson believes that the book seems to give people permission to unpack their grief, to find their inner voice and to take steps forward in the healing process.

“It gives people some of their power back,” she said.

Henricks hopes All Community Reads inspires discussions to take off in a myriad of directions due to the book’s rich content.

“That is what is so special about it,” she said. “You can talk about the criminal justice system, issues with mistaken identities, race or our reliance on stereotypes. I believe the book will have readers asking a lot of questions, and that definitely makes it a good community read with the potential to continue discussions.”

Megan Gloss writes for the Telegraph Herald.