I was born and raised in Wisconsin, and except for a short stint in Chicago in the mid-1990s, it is where I lived my entire life until moving to Dubuque in 2012.

It’s not like Iowa and Wisconsin are so very different. But there is one striking difference that became starkly evident to me the first time visited an Iowa grocery store — somebody moved your cheese.

Seriously, the cheese aisles in Wisconsin grocery stores are significantly more plentiful — vast and never ending — to be exact. (I kept looking and looking for the cheese section at a local grocer’s. Certainly, this half a refrigerator case cannot be it.)

So, with this pedigree coursing through my veins, it would stand to reason that on a recent trip to Italy, I made a pilgrimage to the high temple of cheesedom — Parma. The home of Parmigiano-Reggiano — the king of cheeses.

Parmigiana-Reggiano producers are all located within a zone of production that stretches through the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Mantova and Bologna.

There are about 650 certified Parmigiano-Reggiano producers throughout the region. They belong to a nonprofit consortium that helps ensure the quality and integrity of both the finished product and the production process — which has remained largely unchanged for the past seven centuries.

My pilgrimage started at the Parma train station, where in addition to trains, they have a bike library. It is here I met my guru, Davide, and a retired couple from Canada, Chris and Theresa, who also were taking the tour.

We were outfitted with bikes, then were on our way.

Davide led us through the city to the outskirts of Parma, then into the countryside, past dairy farms and just-harvested alfalfa fields to a small cheese factory.

After donning disposable booties and hairnets, we witnessed the origins of pure cheese genius.

We learned that each batch of cheese is made from the evening milking and subsequent morning milking of nearby Regina cows. The evening milk is set out to settle in large stainless steel settling tables, then the cream is skimmed and used to make butter or other products. The next morning’s milk is added, with all of its cream. This way, they get a naturally part-skim mixture of raw cow’s milk.

It is transferred to large copper-lined conical vats. The vats are sunken below ground and are used to heat the milk mixture to around 95 degrees.

The mixture is left to curdle for 10 to 12 minutes. The curds are broken up into small pieces using an oversized, motorized paddle. The mixture is heated again and allowed to settle for 45 minutes.

Each vat is filled with 1,100 liters of the partial skim milk (291 gallons), which ends up making two, 45 kilograms (100-pound) wheels of cheese.

The cheese curds settle in the bottom of the conical copper tanks, and the cheese makers work it up with a big wooden paddle, then split it into two pieces. Each piece is suspended in muslin and hung from a board over the tank to begin to drain some of the whey. (The leftover whey, incidentally, was traditionally fed to the pigs that would become prosciutto.)

The cheese bundles are then transferred to plastic mold in the shape of a Parmesan wheel and labeled with the date and vat number. Records are meticulous. In case there is some problem with the resulting cheese, it can be traced to a specific batch of milk/cheese.

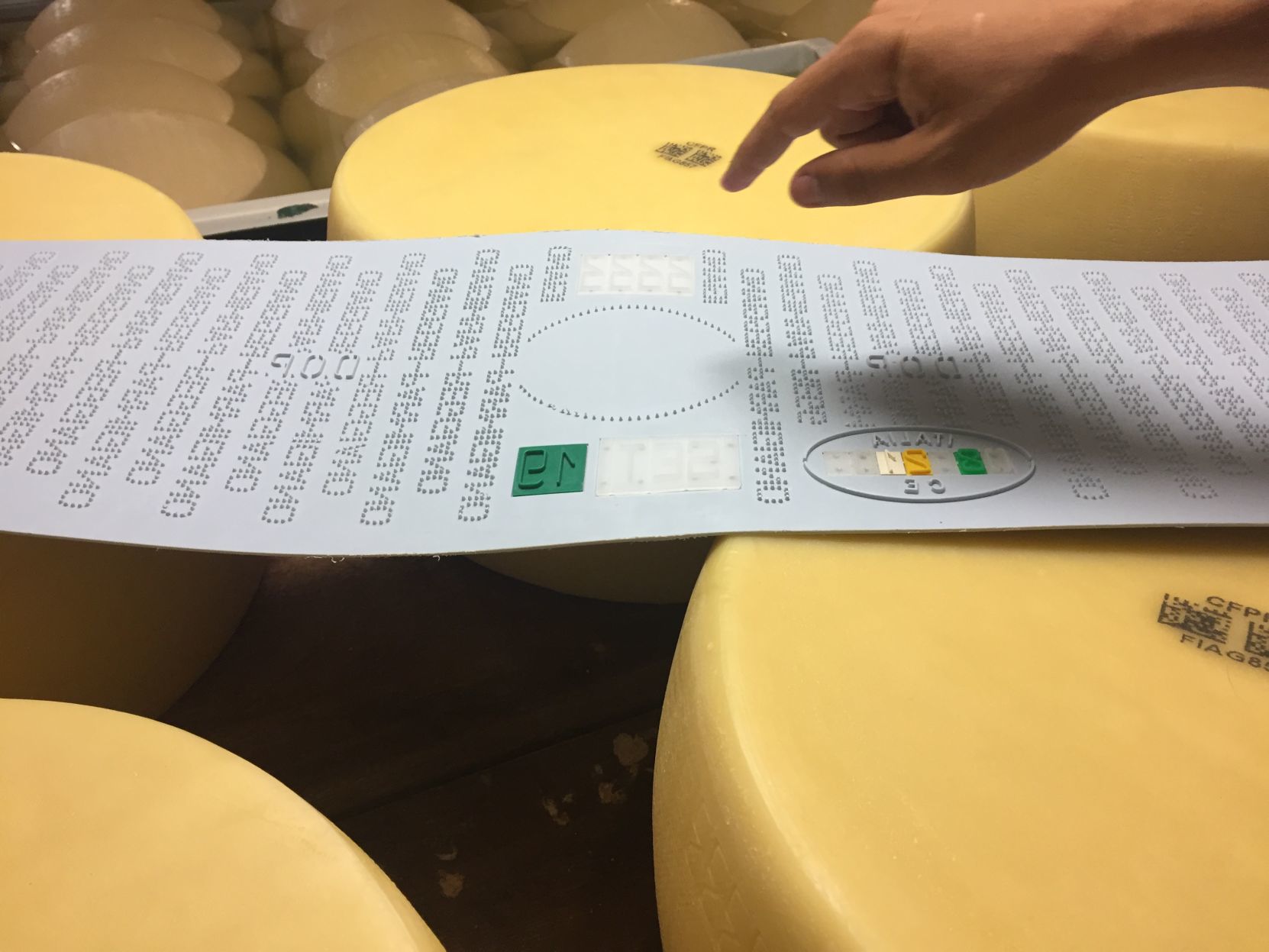

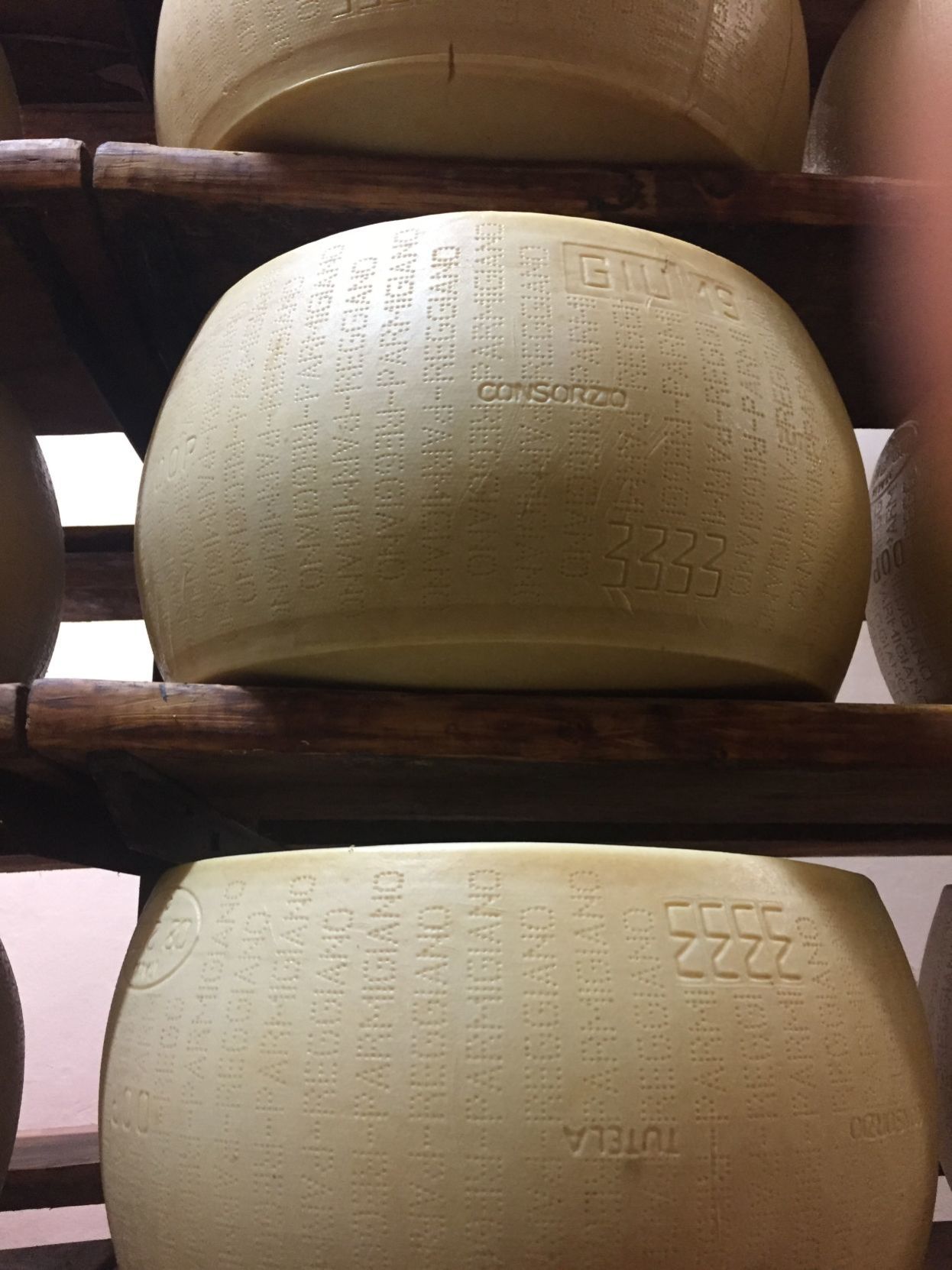

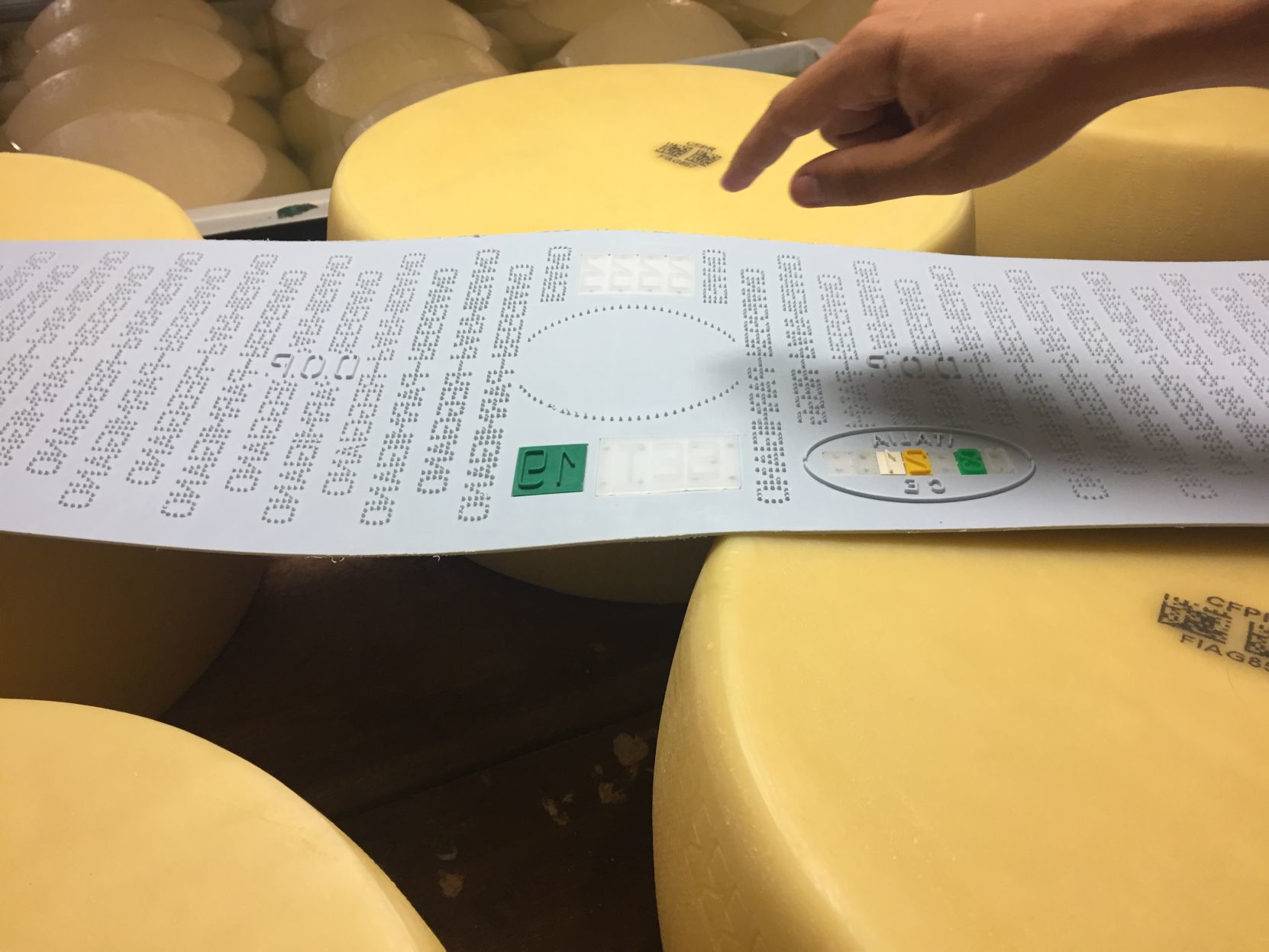

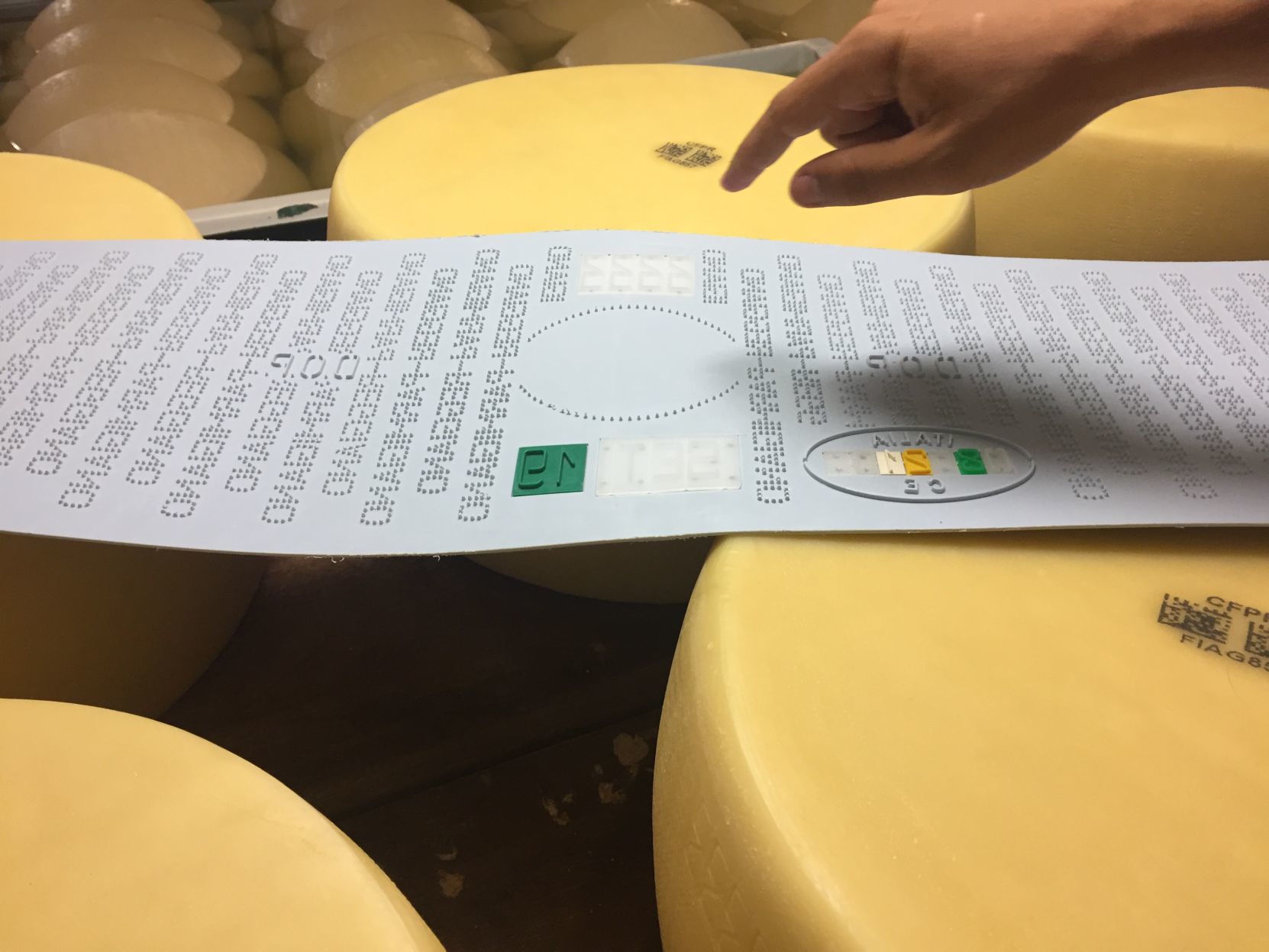

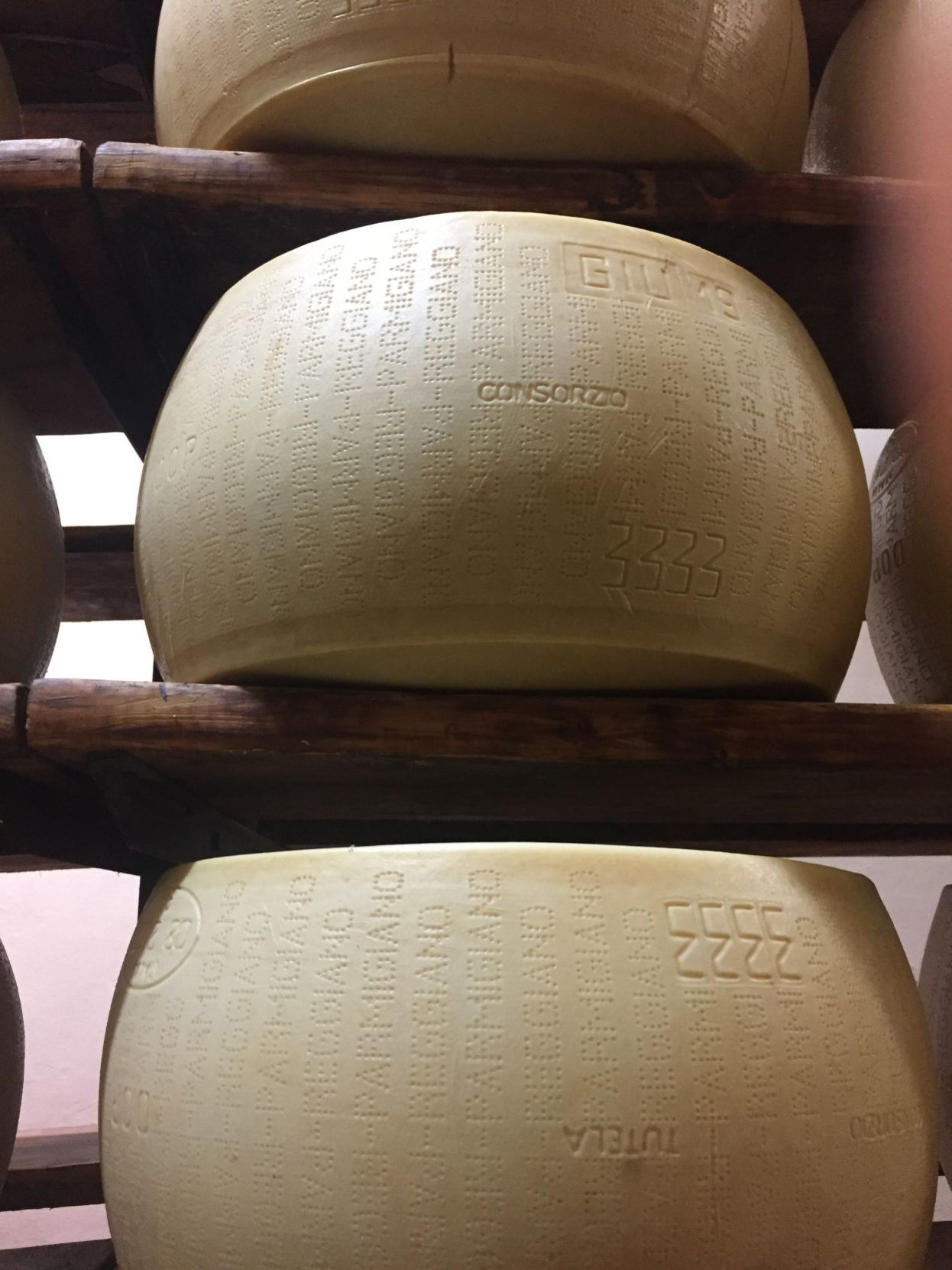

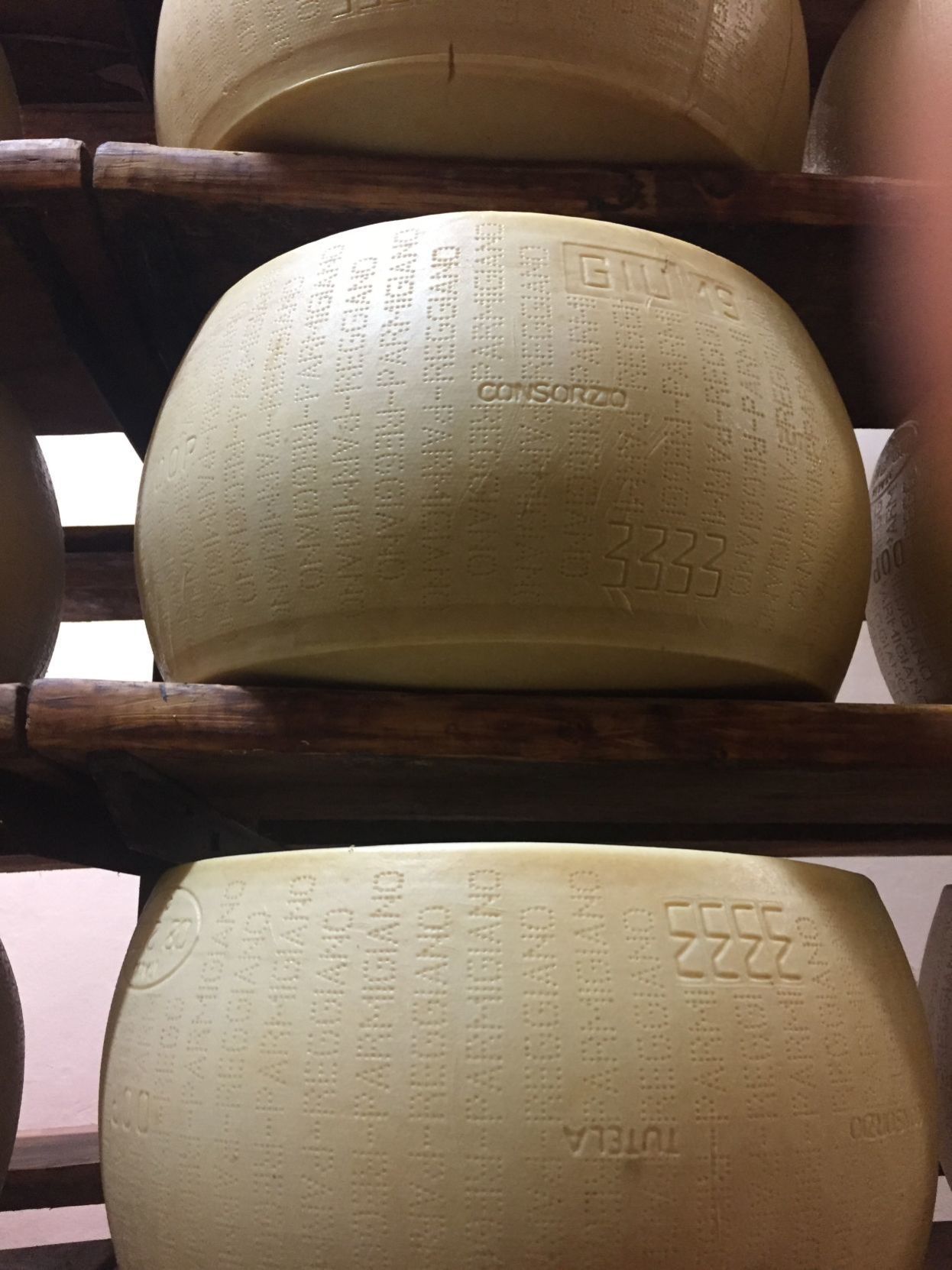

After the cheese is labeled, it rests for a few hours before being put into a stainless-steel band mold for a few days. This is when the wheel really takes its shape. After a couple of days, it is released from this mold and imprinted with the iconic reverse-braille looking writing that marks each wheel with the plant number (ours was 3333), month and year of production.

The wheels are then floated in a salt-water bath for 20 to 25 days, when the salted water works to leach out much of the whey from the cheese.

We were able to taste the cheese at this point in the process — it was rubbery and tasteless — nothing like what it would become after sitting for 12 to 24 months.

The cheese wheels are transferred to the inner sanctum — the aging room. It is a room filled with floor-to-ceiling wooden shelves, stacked with wheels of Parmesan. This is where the cheese will rest for at least the next 12 months, before it can be officially certified as Parmigiano-Reggiano.

After 12 months, the cheese is tested by a certified grader. They tap it with a small, steel hammer to listen for cracks or voids that would allow air to enter the wheel and spoil the cheese.

Wheels that pass the test are then stamped with the official Parmigiano-Reggiano logo, thereby turning it into gold. (A quick internet search revealed that an entire wheel of certified Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese can be purchased in the U.S. for the bargain price of $1,255.88 on Amazon — or $2,499 at Williams Sonoma.)

Incidentally, security is an issue in the aging room. The doors to the outside are secured with a heavy metal bar lock. While cheese robbery is not common, it does happen, especially with prices like that.

After the tour was a tasting. We were able to taste cheese that had been aged for 12, 24 and 36 months. The difference in flavor but particularly in texture was striking. The oldest cheese was strong and very granular, with chunks of crystals throughout. Whereas the younger cheese was smoother and milder in flavor.

And each, as you might suspect, was absolutely delicious.

Leslie Shalabi is co-founder of Convivium Urban Farmstead, a Dubuque-based nonprofit organization based on the idea of creating community around food. A life-long lover of food and entertaining, she is dedicated to helping people find ways to connect through the universal languages of food and hospitality.